Canada 3000 spluttered out of the skies two months after September 11, 2001, stranding 50,000 passengers on five continents, stiffing creditors for a collective $260 million, leaving thousands of Canadians holding $100 million in worthless tickets, putting 4,800 employees out of work just in time for Christmas, and thrusting a hapless Transportation Minister deeper into denial.

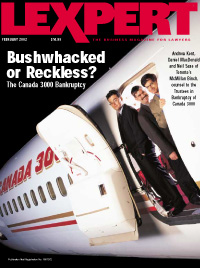

As the federal government, the unions, the former directors and other industry players continue to engage in endless finger-pointing—blaming everything and everyone but themselves for the dramatic failure of Canada’s second-largest airline—Canada 3000’s creditors are already elbows-deep in the airline’s autopsy. “There are some 240,000 claims of one kind or another,” says Andrew Kent at Toronto’s McMillan Binch. The firm is filling the head undertaker role in the bankruptcy proceedings, acting for both Deloitte & Touche and PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP.

The demise of Canada 3000, or at least the speed with which a concerted rescue and restructuring attempt turned into a bankruptcy proceeding, took almost everyone—including Canada 3000, its monitor and their lawyers—by surprise. The company filed for protection under the Companies’ Creditors Arrangement Act (CCAA) on Thursday, November 8. Friday morning saw Canada 3000 grounding all of its airplanes. By Saturday, the company’s board was resigning. A bizarre bankruptcy, neither voluntary nor hostile, was put in place by Sunday.

“Canada 3000 had done no preparation for a bankruptcy. The company was pursuing various negotiations with the government, with its labour unions, but was not preparing for insolvency—no preparatory work on that was done,” says Kent.

About 18 hours after Canada 3000 received CCAA protection, CCAA monitor Deloitte & Touche had to file a material changes report, much to the chagrin of the presiding judge, Mr. Justice John Ground. “The judge was furious with them,” recalls one insolvency lawyer who asked not to be identified.

“It’s fair to say that he expressed concern on Friday afternoon that a company obtained a stay on Thursday afternoon and then was ceasing operations on Friday morning,” Kent cautiously confirms. Mr. Justice Ground’s incredulity was shared by many, including Transport Minister David Collenette, who, as Canada 3000 was sliding into bankruptcy, told the national press that Canada 3000 had “incredible” bookings for the holidays and operations were going on as scheduled.

The only ones prepared for the bankruptcy proceeding appeared to be the airline’s creditors. NAV Canada, the not-for-profit agency that provides navigational services to all aircraft flying in Canadian airspace, had asked its lawyers at Gowling Lafleur Henderson LLP to put together legal teams across the country prepared to bring applications to seize aircraft in all provinces serviced by Canada 3000. “We had teams on stand-by in all offices,” says Christopher Fournier at Gowlings in Ottawa, who is quarterbacking the file for NAV Canada. Canada 3000 had accumulated $7.4 million in unpaid fees to NAV Canada over the months of September and October, and the agency had been reviewing the airline’s account on a weekly basis. The widely reported statements made by John Lecky, Canada 3000’s chairman and largest shareholder, warning that the airline could be out of cash by Christmas, put NAV Canada on high alert.

Other observers were predicting turbulence for the airline in the early summer. “I’ve been looking at Canada 3000 [as a potential target for insolvency] since June,” says Mario Forte, an insolvency lawyer with Ogilvy Renault in Toronto, who is representing the airport authorities of Vancouver, Calgary, Edmonton, Winnipeg, Montreal, Ottawa and Halifax. And, in interviews with Lexpert conducted in June 2001, lawyers and directors connected with WestJet Airlines were seeing Canada 3000’s future as uncertain, and forecast that the Calgary-based short-haul carrier was poised to become Canada’s second-largest airline by attrition. “Do you think Canada 3000 is going to survive? I wouldn’t bet on it.”

A dire outlook for an airline that had been profitable for 12 of its 13 years, with a one-time market capitalization high of $425 million. What happened? Daryl Fridhandler of Burnet, Duckworth & Palmer LLP in Calgary, the lead lawyer for WestJet, thinks the company tried to fix what wasn’t broke, in a race to fill a perceived void in the market. “Canada 3000 did a lot of things to step away from the model that was working for them,” he notes. “First, they moved from a charter carrier to a scheduled carrier. Then, they did two acquisitions—terrible acquisitions—that cost them a lot of money. Between the acquisitions and the move to a scheduled carrier, they just couldn’t reinvent themselves in the time they had.”

As explained by Tom Koutoulakis at Cassels, Brock & Blackwell LLP in Toronto, the acquisitions were part of Canada 3000’s strategy to compete more effectively with dominant carrier Air Canada by increasing its market share in ready-made chunks. Koutoulakis spearheaded the $82 million (in shares) acquisition of Royal Aviation Inc. and the acquisition of IMP Group’s CanJet Airlines on behalf of Canada 3000. “Canada 3000 had the view that it couldn’t ramp up to Air Canada from scratch. Robert Milton, he’s a smart guy, and he has so many planes. You do a good job on a few new routes, he throws a few more planes at them, and drives you off them.” But if you start a whole bunch of routes, well, “he can’t knock you off all of them. So, the only way to increase market share was to acquire chunks—in other words, to buy competitors.”

And the competitors were as ready to be bought as Canada 3000 was ready to buy. Unfortunately for the future of Canada 3000, its first major acquisition was a rough one. “We were not allowed due diligence by Michel Leblanc,” says Koutoulakis. Leblanc was, at the time, the chairman, president and chief executive officer of Royal Aviation. “He kept on saying how Royal and Canada 3000 were competitors and whatever was in Royal’s public record speaks for itself.” Canada 3000 and its lawyers were understandably concerned.

“We decided to add to the public record,” says Koutoulakis. “We argued with McCarthy Tétrault in Montreal [who represented Royal] for days.” But people at Canada 3000 were eager to consummate the deal by the end of March, so that the two airlines would have integrated flight schedules in time for the busy summer season. In the end, even though they did not get the disclosure they wanted, “they went through with the deal. They were given assurances by Michel that the financial statements were cleared—we were not able to go beyond that.”

The deal closed on March 30. Hard on the heels of the Royal acquisition, the company had its legal team working on acquiring CanJet from IMP within a few days. Again, the acquisition was to be completed on the QT, so that Canada 3000, Royal and CanJet would be one by the summer.

When summer came around, it was obvious that Canada 3000 had bitten off more than it could chew. Cash flow wasn’t great. On July 31, Canada 3000 had barely enough cash for 20 days of operations, even though it had taken in 26 days worth of tickets ($82 million in cash available to $106 million in liabilities for prepaid flights).

But it was the Royal acquisition—or rather, the discrepancy between what it laid out and what it got—that was particularly sticking in its craw. By August, Canada 3000 was suing Royal Aviation, Leblanc and Roland Blais, who was Royal’s executive vice-president and chief financial officer during the acquisition, according to its Statement of Claim, for $40 million in damages for “fraud, negligence, breach of contract, conspiracy, fraudulent or intentional misrepresentation and/or negligent misrepresentation in respect of the financial status, financial statements and other financial records of Royal Aviation Inc.”

Leblanc and Blais, represented by the Montreal office of McCarthy Tétrault LLP, launched a countersuit. Between exchanging Statements of Claim, Canada 3000 continued its attempts to integrate three separate airlines, each heavily unionized, into one functioning unit in the face of a softening economy, continued cash flow problems and intensified competition from Air Canada.

“They were dealing with three things,” says Koutoulakis. “One, they had to weather the recession. Two, there was a historic low in the Canadian dollar and all lessors had to be paid in American dollars. And then, you had Air Canada standing on your head. Things were tough, but they would have gotten over the hump. Sales were good.” On September 10, Canada 3000 sold 25,000 tickets—an all-time high. The next day, the aviation industry worldwide received a crippling blow, with airlines collapsing throughout Europe and Australia within weeks of the September 11 terrorist attacks.

In Canada, Air Canada immediately cut flights by 30 per cent and laid off 5,000 employees. It had already laid off 7,500 employees during the past year. Air Transat, significantly smaller than Canada 3000, cut 1,300 jobs. And, while domestic short-haul carrier WestJet announced another consecutive profitable quarter, Canada 3000 floundered, and, like Air Canada, it looked to the federal government for help. A generous precedent had been set by the United States, which offered a US$15 billion aid package, including both cash and loan guarantees, to its airlines. When Transportation Minister David Collenette announced the Canadian equivalent—$160 million meant to compensate the airlines for days lost due to closed airspace—airlines reeled again. At best, Canada 3000 would get $10 million, and according to its officers, it simply wasn’t enough.

“Canada 3000 was in Ottawa all the time at this point, going through hoops to get the little they would get,” says Koutoulakis. “And then they started to get into a queue—kind of take a number situation—to get more.” It was at this point that Lecky, Canada 3000’s chairman, made an astounding move. On October 15, he told reporters Canada 3000 would be out of money by Christmas unless the government came through with an adequate bail-out package. His statements took both the federal government and Canada 3000 by surprise—apparently Lecky acted independently without consultation with the airline’s president, Angus Kinnear, or other members of the board.

The immediate result was a seriously annoyed government and panicked creditors. As airport authorities in Canada and around the world retained lawyers and prepared to seize Canada 3000 aircraft, the Department of Transportation (informally) asked members of the Canadian Airports Council to hold off. Late in the evening of October 25, Collenette announced a $75 million loan guarantee for Canada 3000. Creditors breathed easier, and, for a few hours, it looked like Lecky’s gamble had paid off for Canada 3000. Then the airline saw the term sheet.

“I found it to be a fairly aggressive term sheet,” says Koutoulakis who, along with partner Renate Herbst, had the unenviable job of reporting on the terms of the loan guarantee to Canada 3000’s board of directors. “The conditions attached were unexpected from a government entity. It looked more like conditions I would expect to see in a capital venture deal or something like that, but not in a government assistance offer in the wake of 9/11.”

Canada 3000 officials said privately and publicly that the financial conditions were “severe and almost unworkable.” Although the term sheet is not in the public record, it is understood that the $75 million loan hinged on such conditions as demanding that investors inject $10 million in new capital, entitling the government to acquire one-sixth of the airline, and charging Canada 3000 an annual interest rate of 6 per cent in addition to the rate it would have to pay to a commercial bank. The real hurdle, however, proved to be the requirement to provide Ottawa with a viable business plan that showed a return to profitability. With passenger traffic falling off by 30 per cent, creditors clamouring for payment and the government bail-out fraught with conditions, Canada 3000 decided to take drastic action—eliminate the just-acquired Royal and the 1,500 people it employed.

The acquisitions of Royal and CanJet left Canada 3000 with numerous unions, collective agreements and differing levels of seniority and pecking orders, which it had been at some pains to integrate. William Phelps, Q.C., at Toronto-based Mathews, Dinsdale & Clark LLP, long-time labour advisor to the airline and negotiator of its first collective agreements, had spent several months working with the unions of CanJet, Royal and Canada 3000, attempting to integrate the employees into one body with streamlined union representation and collective agreements.

“There was a lot of work to sort this all out,” says Phelps, “and it was done successfully. Everyone involved would say so—there was no one party who won and others who lost. It was a good solution for everyone. I thought, great, we got that behind us.” The only task left was an appeal to the Canada Industrial Relations Board (CIRB) to restructure the three sets of unions representing pilots, flight attendants and other airline employees into one set. All the unions were on board. With that on his mind and a government loan guarantee in the background, Phelps flew his family, on Canada 3000, to Florida for a long overdue vacation. “The day after, I got a call telling me we may be in bankruptcy unless we can lay off a third of our employees.

“It all went back to the loan guarantees. To stay in business, we needed the loan guarantee. To get the loan guarantee, we had to have a viable business plan. To get a viable business plan, we needed to have staff reductions—we had to cut down the size of the airline by 30 per cent. The quickest and easiest way to do that was to separate Royal, which was still functioning as a virtually separate company, and end it.” For Phelps, this meant undoing the integration work of the summer, and asking the CIRB to permit Canada 3000 to treat Royal as a separate unit again. “All of a sudden, our position regarding the integration of the three airlines changed. We’re no longer going to integrate Royal, we now wanted to put it out of business…. Without a CIRB order, if we stopped Royal, Royal employees could bump Canada 3000 employees”—that is, laid-off pilots, flight attendants and other unionized employees with seniority could displace less senior personnel throughout Canada 3000 and the merged CanJet. The process would be disruptive, but, more importantly for Canada 3000, it would be expensive.

“Royal had the least suitable aircraft and was doing the type of flying that would have to go, in terms of the routes, the operating costs of the aircraft, the number of seats and so on,” explains Phelps. The difference in aircraft had huge implications for Canada 3000’s cost-cutting measures. “To train a Royal pilot to go from flying an Airbus 310 to a different aircraft, say an Airbus 329 or 320, would cost approximately $50,000 per pilot.” Multiply that by 150 Royal pilots, and “it was prohibitively expensive for a company already starved for cash.”

The CIRB process started on Monday, November 5. On Wednesday at noon, the CIRB ruled against Canada 3000, or rather, “The board said we’re not going to make this decision, you guys negotiate,” says Phelps. And negotiate they did, late into Wednesday night.

“We finally got agreements with the pilots. It was late, but it was not too late,” says Phelps. But it was not enough. Agreement with the Canadian Union of Public Employees (CUPE), the union representing the most employees at Royal, proved impossible. In Phelps’s opinion: “This is where CUPE has misled the press. They said they agreed to 500 layoffs. Yes, they did. But they wanted a guarantee that there would be no more layoffs, and how could the company guarantee that in the present climate? And they would not agree that these people be laid off until they were cross-trained, which would take four to six weeks, as any cross-training program would have to be government approved. And the company simply did not have that kind of time.”

According to Phelps, “That’s what really took it down. Otherwise, we would have had the documentation on the government’s table by Thursday morning. I’m told we would have had the loan guarantees, and we could have continued.”

Michael Church at Caley & Wray, who is representing CUPE in the current bankruptcy proceedings, believes that although “the union would not agree to [laying off all Royal employees], it would not have saved Canada 3000 anyway.” The company was in bad shape before September 11, he says, and those events only made a bad situation worse. Moreover, according to their lawyers, the unions never did know how bad things really were.

“The first day in court before Justice Ground, one of the union lawyers came up to me and asked, ‘Is Canada 3000 really in trouble?’” recalls Koutoulakis. “We’re in court filing for bankruptcy protection—what do you think?” was the reply.

“I was surprised by the speed with which the company went under and the magnitude of the company’s problems,” says Church. “Whoever was responsible did a good job of keeping things under wraps. I’m not blaming them—once people know, they’ll stop booking. Employees would have known in normal course, but in this case, did not. With the benefit of hindsight, the company should have come to the unions sooner and been more frank. The government never did come to the unions, and by the time the company came to the unions, it was basically over.”

According to Phelps, the unions had the facts. Some of them just chose not to believe them. “We had been telling them that for 18 hours. We told them we’d be in bankruptcy court on Thursday, and they told us not to make threats. ‘Don’t try to push us into a fast decision,’ they said. I said, ‘We’re not going to push you, the bankruptcy court is.’”

The proposal by the former owner of Royal to buy back the airline—at $25 million—threw a wrench into the negotiation process. “Leblanc fired over an offer letter, but to my knowledge, it was not considered and no one negotiated with him at all. His offer was highly conditional and was dismissed for a number of factors,” explains Koutoulakis. “Among the conditions was a government loan guarantee [for $30 million]…the board looked at it and felt it was so highly conditional as to not even be an offer. We were pretty annoyed.”

Leblanc’s “red herring” aside, the dire financial position of the company, says Phelps, “was certainly communicated to [the unions] under oath by the president of the company.… I told them myself about three times that night. CUPE thought we were bluffing.”

“They were very frank at the end,” admits Church. Unfortunately, by then it was too late. Canada 3000 walked away from the table frustrated and disheartened. It proceeded to apply for CCAA protection on Thursday, but without the union concessions needed to shut down Royal—the company had explored no other options—the $75 million loan guarantee was moving farther out of its reach. A press release issued at 5 p.m. that night—without the approval of Kinnear—informed customers that CCAA protection was granted, and the company would continue to operate. But that night, everything changed, and by Friday morning, Canada 3000’s airplanes were not flying.

“We were retained by Deloitte & Touche on Thursday morning, reviewed the order at lunch, and went to court that afternoon to get CCAA protection,” recalls Andrew Kent. “On Friday morning, the airline had shut down. On our advice, Deloitte & Touche filed a material changes report and Canada 3000 asked for time, over the weekend, to sort out what it was going to do. By Saturday, it looked like the company’s board was in the process of resigning.” Saturday and Sunday found the team at Deloitte & Touche, led by Kurt Bonokoski, and the team at McMillan Binch desperately trying to put together a bankruptcy.

“To put a company into voluntary bankruptcy, you need to have a resolution by the board of directors. There was no board. A hostile bankruptcy needs to be initiated by a creditor—there was no creditor initiating that,” explains Kent. Pressed for time, Mr. Justice Ground approved an option put forward by McMillan Binch and Deloitte & Touche “giving the monitor the authority to put the company into voluntary bankruptcy.” The monitor then had to find an official receiver to accept a bankruptcy assignment on Sunday evening. By Monday, November 12, two-and-a-half weeks after Collenette’s not-so-guaranteed loan guarantee, a week and a half since Tango’s first flight, four days after negotiations with CUPE failed, and two months after 9/11, Canada had one less airline in its skies. It would take some time before Canadians—including the Transportation Minister and the Competition Bureau Commissioner—would accept this.

As Deloitte & Touche informed the court that despite the CCAA protection that stipulated the airline continue operations, Canada 3000 had grounded all its planes and Konrad von Finckenstein, Q.C., announced that the Competition Bureau was just about to put a cease and desist order on Air Canada’s Tango in response to Canada 3000’s October 12 complaint. “Sweet, eh?” comments Koutoulakis. “It was totally disheartening. Why are you saying this? You know this can’t help us—it can’t help anyone. I still can’t understand why they didn’t issue the cease and desist order. If it didn’t help Canada 3000, it could have helped some other people. The timing was incredulous.”

“The timing of the bureau’s announcement regarding Tango was unfortunate,” concurs Gordon Capern of Paliare Roland Rosenberg Rothstein LLP, representing the Greater Moncton Airport Authority. “All it did was demonstrate that the Competition Bureau cannot deal with these issues in a timely fashion. It was ironic.”

Fridhandler at Burnet, Duckworth & Palmer thinks that’s an understatement. “It was just garbage. Easy to say that after the fact,” especially when the end result was that the Competition Bureau didn’t do anything, as the affected party, having been permanently knocked out of the sky, was no longer being hurt. But, says Fridhandler, “Canada 3000 was on its way out anyway. Tango didn’t do it. It may have been the final nail in the coffin, but it didn’t do it.”

Koutoulakis doesn’t think Tango knifed Canada 3000 either. But Air Canada—that’s a different story. “Tango as Tango was only flying for a few days,” he says. “The big question is, was Air Canada a factor? Tango is just one and the latest arrow in their quiver.” And, although he sees Air Canada’s behaviour as “categorically” anti-competitive, his major beef is not with Air Canada. It is with the regulated but unenforced environment in which the game is played out.

“Would I call what they do anti-competitive in an open market? No,” says Koutoulakis. “Ruthless, but good business. As an MBA or a business person, do I think Tango is a good idea? How can you not? But if the federal government puts these rules, calls certain practices predatory behaviour—then yeah, it’s anti-competitive.”

Capern agrees that “Air Canada has demonstrated extreme anti-competitive behaviour.” And, most pertinently, “The Competition Bureau has been unable to deal with it for the last 10, 15 years.” WestJet’s director of public relations and communications Siobhan Vinish concurs, and calls for “a Competition Act with teeth to it to ensure competition.”

If the Competition Bureau is ineffective, the federal government can best be characterized as confused. Says Mario Forte at Ogilvy Renault, “Part of the problem was the government sticking its oar in the water. It created a false impression.” Lawson Hunter, Q.C., formerly a commissioner of the Competition Bureau and presently senior competition counsel with the Air Canada team at Stikeman Elliott, believes the federal government should never have gotten involved in the aviation industry in the first place. “They got involved once,” he says, “and now they feel they have to keep on doing something.” Unfortunately, it frequently appears that they have no idea what that something is.

The precedent of meddling creates certain expectations. “I thought there was going to be some financing by the government,” admits David Kee of Blake, Cassels & Graydon LLP in Toronto, who is representing Royal creditor CIBC. Given the government’s past behaviour in respect of Hunter’s client, the expectation was not unusual. Says Capern, “Not to say that Canada 3000 was not the author of its own misfortune, but it seems that Air Canada can make one mistake after another [and it gets bailed out], but every other airline makes one management mistake and it pays immediately.”

As Collenette finally came to terms with the fact that Canada 3000 would not fly again, he assured Canadians that the federal government “absolutely did as much as we could.”

Perhaps it did. Phelps doesn’t have any issues with the conditions attached to the not-so-guaranteed loan guarantee. His issue is with the unions—or, more specifically, “Two or three very militant, vocal people at CUPE pushing their opinions on everyone. They led the bargaining committee astray” and effectively hijacked the proceedings. “I have great trouble understanding the logic of, ‘We’re going to refuse to make concessions to the employer to keep the employer alive even if it takes the airline down.’ Are you better off with 10 to 20 per cent of your people out of work for two months or everyone out of work permanently?” In addition to representing flight attendants at Canada 3000, CanJet and Royal, CUPE is also the bargaining agent for flight attendants at Air Canada. And that raises an interesting question.

“Whether they did not believe us or whether they were afraid if they agreed to this with Canada 3000, they might have set a precedent for Air Canada, who they also represent, I don’t know,” says Phelps. But if they did, “they effectively sacrificed the Canada 3000 people for the Air Canada people.”

So, bushwhacked or reckless? Who is to blame? Unreasonable unions, a federal government ineptly playing business hardball, a well-meaning but ineffectual Competition Bureau, a ruthlessly anti-competitive Air Canada, a softening economy, or 9/11? Daryl Fridhandler is blunt: “They did it to themselves.” And, as Capern puts it, it is hard not to see Canada 3000 as the author of its own misfortune.

While its directors could not have predicted 9/11, it is hard to see the acquisition of Royal as a prudent move—particularly as Canada 3000’s August Statement of Claim against Royal makes clear, there were concerns about the acquisition’s finances and disclosures throughout the negotiations. The apparent lack of communication between Lecky and Kinnear, demonstrated by Lecky’s revelations about the company’s financial status on October 15, and subsequent (mis)communication of events during the company’s weekend of crisis, must have had an effect on the strategic efficacy of the company. Lecky’s October 15 statements may have been intended as a spur to the federal government; but their first and most lasting result was to jitter creditors, domestic and international. The calls for cash could be staved off for a while with assurances that a government bail-out was coming, but most airport authorities weren’t willing to take that chance. And, as Lawson Hunter, with massive understatement, deadpans “Once people start seizing planes, it’s over.”

The end for Canada 3000 meant the beginning of a long and protracted process for its many creditors and lessors, jockeying for a piece of whatever remained. And the process is not a happy one. “I hate it,” says Forte. “If you find anybody who says otherwise, they’re lying. There are no happy faces on this file.”

One of the first and most positive accomplishments of the creditors was getting pay cheques to Canada 3000’s employees. Says McMillan Binch’s Neil Saxe, “There was every intention [on Canada 3000’s part] to pay its employees. Everyone had that expectation. It seemed the right thing to do, to get these people their last pay cheque. We worked with everyone, and everyone co-operated.” The company had about $20 million in a Royal Bank of Canada account and RBC, one of the few secured creditors in the matter, “was willing to take the risk.” On November 22, with the full co-operation of RBC and other creditors, the Ontario Superior Court of Justice released $6.3 million from the account for payment of back wages to the airline’s 4,800 employees.

“It was an unusual thing, but right thing to do,” says Kent. And, while some creditors may have had private reservations about releasing that much money so early in the process, “No one was prepared to say ‘no,’ publicly.”

The court order was good news for Canada 3000 employees, but potentially bad news for its ex-directors. “When the court authorized the employees to be paid, it reserved the right for them to seek redress,” explains Kent. In other words, “Directors still have some personal liability.” And the mystery of the en masse November 10 resignation, Kent believes, is best understood as “a fundamental conflict between operations and liability.”

“In this case it’s clear that the resignations were motivated by a concern regarding personal liability. The company had about $20 million in the bank…. It was losing cash daily, and the directors didn’t want to see the money spent,” says Kent. Continuing operations meant continuing to spend money, and the less money Canada 3000 had when the end finally came—as seemed inevitable by the first week of November—the more personal liability its directors would have. The rapid dissolution of the board was their inelegant solution, the efficacy of which is still to be tested in the courts.

Once the employees received their last pay stub—severance, termination, benefits and other employee claims remain outstanding—Deloitte & Touche decided to step aside as trustee in bankruptcy. It had been filling the peculiar dual role of monitor under the CCAA and trustee in the bankruptcy since the crisis weekend. On November 16, as the remainder of Canada 3000 subsidiaries, including Canada 3000 Holidays, Canada 3000 Tickets and Royal Handling Inc. made assignments in bankruptcy, PwC came into play as their trustee in bankruptcy. On November 30, the court approved Deloitte & Touche’s request that it be replaced as trustee by PwC.

“Under the statute, if you’ve been an auditor of a firm within two years, you should not be its trustee in bankruptcy,” explains Neil Saxe. “There’s a specific provision in the CCAA that you can be a monitor even if you were an auditor.” When Canada 3000’s CCAA protection turned into a bankruptcy, “There was nobody in charge of the assets. Deloitte & Touche was there, and it made sense for Deloitte & Touche to fill the role of trustee.” The bankruptcy statute does provide for such a case, with the court’s approval. And the court was pleased to approve. “But Deloitte & Touche was still concerned about its position according to its own professional standards.” It stepped down, and PwC, under the leadership of Karen Cramm, took over. McMillan Binch remained as legal advisor through the change of trustees, providing continuity.

Continuity was sorely needed, as the “priority dispute” among the major creditors came into full swing. The first set of battle lines was drawn between owners of aircraft leased to Canada 3000 and the airport authorities and NAV Canada. The burning issue—who has rights to the planes? The immediate issue—what to do with Canada 3000’s 42 aircraft, which, although grounded, needed ongoing maintenance and care?

“The first skirmish was to release the aircraft,” says Michael Rotsztain at Torys LLP, representing US Airways, which leased 11 airplanes to Canada 3000. “There’s a fair amount of solidarity among the lessors,” whose right to their aircraft is contested by NAV Canada and the airport authorities. “NAV Canada and the airport authorities, to varying degrees, claim that they were victims of timing, that the CCAA filing froze their rights to apply for seizure,” explains Rotsztain. But before the main engagement between the two parties would settle this issue, the lessors wanted to get their planes back, re-lease them if possible, and thus not compound their losses. In short, says Michael Feldman also at Torys, who is working with lessors US Airways, International Lease Finance Corporation and Aviation Capital Group, “These are our aircraft and we want them back.”

Mr. Justice Ground obliged, and as the lessors posted securities, bonds and letters of credit—in case NAV Canada and the other parties were successful in subsequent litigation—planes were gradually released and re-leased. But the main event, which would establish whether NAV Canada and the airport authorities did indeed have seizure rights to lessors’ aircraft, was just starting in late December.

“Our position is that NAV Canada is a secured creditor because of the seizure rights,” explains Fournier at Gowlings. “Section 55 [of the Civil Air Navigation Service Commercialization Act, CANSCA] makes the owner and operator for aircraft jointly liable. Section 56 gives to NAV Canada the right to seize aircraft in respect of which charges have arisen.” These rights, says Fournier, apply to any aircraft owned and operated by the person owing money, not just the specific aircraft to which the charges apply. “The lessors are saying they are not owners as defined in this Act and therefore not liable to make payment. That issue has arisen in the InterContinental case in Quebec.” In that airline bankruptcy case, the Quebec Superior Court found in favour of the position taken now by NAV Canada. The case, however, is under appeal and is unlikely to be resolved before a decision on the Canada 3000 case is made. “Laws will be formed by this case,” says Fournier.

From the opposite side, Rotsztain agrees. “It’s an important case for the airline industry. What kind of country is Canada if you are just a lessor and you find yourself subject for navigation fees, airport charges, etc.? You have no way to protect yourself.”

“The decision of the lower courts will not be final,” predicts Fournier. “There will be appeals.”

In other words, as Forte says, “We may all be getting old on this.”

While NAV Canada and the lessors duke it out, other creditors are taking a back seat. “We’re taking a low profile because our assets in Royal are not substantial,” Kee explains CIBC’s position.

AMEX Bank of Canada, represented by Deborah Glendinning from Osler, Hoskin & Harcourt LLP, is likewise “just monitoring what is happening.”

The trustee, too, whose job it is “not to take sides, but to make sure things are done right,” is watching from the sidelines. McMillan Binch’s lead litigator on the file, Daniel MacDonald “is trying to stay out of it as much as possible, because it’s a real cat fight right now,” says Kent.

The cat fight is now taking place solely under the auspices of the bankruptcy proceedings. The CCAA protection was terminated on December 7. “It was useful while it was there, because it provided stability, kept people from grabbing things, and kept open the possibility of reorganization,” says Kent. “But it became clear to the monitor from the proposals offered that we’d be looking at a sale of pieces, not a reorganization of the whole.”

A number of interested parties, including Kinnear and Leblanc, have approached the monitor, the trustee and the unions with tentative proposals. The group working with Deloitte & Touche, which is said to include former Canada 3000 executives and investors, is considering leasing 10 Airbus A320s and possibly using the Canada 3000 name. Deloitte & Touche’s Michael Badham has been quoted in the national press as saying, “Our own sense is there’s a lot of value in the Canada 3000 name. It is associated with reliable, affordable service.” Needless to say, there are 50,000 Canadians who were stranded around the globe in mid-September of last year who may disagree with Mr. Badham.

However, before a phoenix rises from Canada 3000’s ashes, potential investors have one concern: “What is the government’s policy going to be vis-à-vis Air Canada?” asks Kent. “If it’s fine for Air Canada to use a Tango or another ‘fighting brand’, what’s the point of investing? There’s a plan and a willingness to finance that plan right now, but the key point is, what is the government’s policy?”

In the wake of this and other uncertainties, Koutoulakis is very cautious about any future Canada 3000 phoenixes. “Air Canada’s still out there, we still have the recession, the dollar still sucks. Anyone who starts an airline right now—what can I say, God bless.”

For now, as the aviation industry shakedown continues, the federal government ponders its next tremulous step, and potential investors bide their time, Canadian consumers have less choice and more worry.

“We’re at the mercy of Air Canada,” says Phelps. And like Canada 3000, Air Canada is at the mercy of a confused federal government, a heavily unionized labour force, and free market economic forces with which it appears unable to cope.

Says Fridhandler, “Someone’s got to be keeping an eye on their cash reserves. I’m sure taxpayers of this country won’t want to bail them out.”

Should the national carrier ever require an obituary, it could not aspire higher than to the last words said about Canada 3000 by competitor WestJet. Eulogizes Vinish, “Canada 3000 was a good airline. It provided good service. The marketplace will miss it.” Amen. We await with anticipation for whatever may arise from its ashes.

Marzena Czarnecka is a Lexpert staff writer.

As the federal government, the unions, the former directors and other industry players continue to engage in endless finger-pointing—blaming everything and everyone but themselves for the dramatic failure of Canada’s second-largest airline—Canada 3000’s creditors are already elbows-deep in the airline’s autopsy. “There are some 240,000 claims of one kind or another,” says Andrew Kent at Toronto’s McMillan Binch. The firm is filling the head undertaker role in the bankruptcy proceedings, acting for both Deloitte & Touche and PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP.

The demise of Canada 3000, or at least the speed with which a concerted rescue and restructuring attempt turned into a bankruptcy proceeding, took almost everyone—including Canada 3000, its monitor and their lawyers—by surprise. The company filed for protection under the Companies’ Creditors Arrangement Act (CCAA) on Thursday, November 8. Friday morning saw Canada 3000 grounding all of its airplanes. By Saturday, the company’s board was resigning. A bizarre bankruptcy, neither voluntary nor hostile, was put in place by Sunday.

“Canada 3000 had done no preparation for a bankruptcy. The company was pursuing various negotiations with the government, with its labour unions, but was not preparing for insolvency—no preparatory work on that was done,” says Kent.

About 18 hours after Canada 3000 received CCAA protection, CCAA monitor Deloitte & Touche had to file a material changes report, much to the chagrin of the presiding judge, Mr. Justice John Ground. “The judge was furious with them,” recalls one insolvency lawyer who asked not to be identified.

“It’s fair to say that he expressed concern on Friday afternoon that a company obtained a stay on Thursday afternoon and then was ceasing operations on Friday morning,” Kent cautiously confirms. Mr. Justice Ground’s incredulity was shared by many, including Transport Minister David Collenette, who, as Canada 3000 was sliding into bankruptcy, told the national press that Canada 3000 had “incredible” bookings for the holidays and operations were going on as scheduled.

The only ones prepared for the bankruptcy proceeding appeared to be the airline’s creditors. NAV Canada, the not-for-profit agency that provides navigational services to all aircraft flying in Canadian airspace, had asked its lawyers at Gowling Lafleur Henderson LLP to put together legal teams across the country prepared to bring applications to seize aircraft in all provinces serviced by Canada 3000. “We had teams on stand-by in all offices,” says Christopher Fournier at Gowlings in Ottawa, who is quarterbacking the file for NAV Canada. Canada 3000 had accumulated $7.4 million in unpaid fees to NAV Canada over the months of September and October, and the agency had been reviewing the airline’s account on a weekly basis. The widely reported statements made by John Lecky, Canada 3000’s chairman and largest shareholder, warning that the airline could be out of cash by Christmas, put NAV Canada on high alert.

Other observers were predicting turbulence for the airline in the early summer. “I’ve been looking at Canada 3000 [as a potential target for insolvency] since June,” says Mario Forte, an insolvency lawyer with Ogilvy Renault in Toronto, who is representing the airport authorities of Vancouver, Calgary, Edmonton, Winnipeg, Montreal, Ottawa and Halifax. And, in interviews with Lexpert conducted in June 2001, lawyers and directors connected with WestJet Airlines were seeing Canada 3000’s future as uncertain, and forecast that the Calgary-based short-haul carrier was poised to become Canada’s second-largest airline by attrition. “Do you think Canada 3000 is going to survive? I wouldn’t bet on it.”

A dire outlook for an airline that had been profitable for 12 of its 13 years, with a one-time market capitalization high of $425 million. What happened? Daryl Fridhandler of Burnet, Duckworth & Palmer LLP in Calgary, the lead lawyer for WestJet, thinks the company tried to fix what wasn’t broke, in a race to fill a perceived void in the market. “Canada 3000 did a lot of things to step away from the model that was working for them,” he notes. “First, they moved from a charter carrier to a scheduled carrier. Then, they did two acquisitions—terrible acquisitions—that cost them a lot of money. Between the acquisitions and the move to a scheduled carrier, they just couldn’t reinvent themselves in the time they had.”

As explained by Tom Koutoulakis at Cassels, Brock & Blackwell LLP in Toronto, the acquisitions were part of Canada 3000’s strategy to compete more effectively with dominant carrier Air Canada by increasing its market share in ready-made chunks. Koutoulakis spearheaded the $82 million (in shares) acquisition of Royal Aviation Inc. and the acquisition of IMP Group’s CanJet Airlines on behalf of Canada 3000. “Canada 3000 had the view that it couldn’t ramp up to Air Canada from scratch. Robert Milton, he’s a smart guy, and he has so many planes. You do a good job on a few new routes, he throws a few more planes at them, and drives you off them.” But if you start a whole bunch of routes, well, “he can’t knock you off all of them. So, the only way to increase market share was to acquire chunks—in other words, to buy competitors.”

And the competitors were as ready to be bought as Canada 3000 was ready to buy. Unfortunately for the future of Canada 3000, its first major acquisition was a rough one. “We were not allowed due diligence by Michel Leblanc,” says Koutoulakis. Leblanc was, at the time, the chairman, president and chief executive officer of Royal Aviation. “He kept on saying how Royal and Canada 3000 were competitors and whatever was in Royal’s public record speaks for itself.” Canada 3000 and its lawyers were understandably concerned.

“We decided to add to the public record,” says Koutoulakis. “We argued with McCarthy Tétrault in Montreal [who represented Royal] for days.” But people at Canada 3000 were eager to consummate the deal by the end of March, so that the two airlines would have integrated flight schedules in time for the busy summer season. In the end, even though they did not get the disclosure they wanted, “they went through with the deal. They were given assurances by Michel that the financial statements were cleared—we were not able to go beyond that.”

The deal closed on March 30. Hard on the heels of the Royal acquisition, the company had its legal team working on acquiring CanJet from IMP within a few days. Again, the acquisition was to be completed on the QT, so that Canada 3000, Royal and CanJet would be one by the summer.

When summer came around, it was obvious that Canada 3000 had bitten off more than it could chew. Cash flow wasn’t great. On July 31, Canada 3000 had barely enough cash for 20 days of operations, even though it had taken in 26 days worth of tickets ($82 million in cash available to $106 million in liabilities for prepaid flights).

But it was the Royal acquisition—or rather, the discrepancy between what it laid out and what it got—that was particularly sticking in its craw. By August, Canada 3000 was suing Royal Aviation, Leblanc and Roland Blais, who was Royal’s executive vice-president and chief financial officer during the acquisition, according to its Statement of Claim, for $40 million in damages for “fraud, negligence, breach of contract, conspiracy, fraudulent or intentional misrepresentation and/or negligent misrepresentation in respect of the financial status, financial statements and other financial records of Royal Aviation Inc.”

Leblanc and Blais, represented by the Montreal office of McCarthy Tétrault LLP, launched a countersuit. Between exchanging Statements of Claim, Canada 3000 continued its attempts to integrate three separate airlines, each heavily unionized, into one functioning unit in the face of a softening economy, continued cash flow problems and intensified competition from Air Canada.

“They were dealing with three things,” says Koutoulakis. “One, they had to weather the recession. Two, there was a historic low in the Canadian dollar and all lessors had to be paid in American dollars. And then, you had Air Canada standing on your head. Things were tough, but they would have gotten over the hump. Sales were good.” On September 10, Canada 3000 sold 25,000 tickets—an all-time high. The next day, the aviation industry worldwide received a crippling blow, with airlines collapsing throughout Europe and Australia within weeks of the September 11 terrorist attacks.

In Canada, Air Canada immediately cut flights by 30 per cent and laid off 5,000 employees. It had already laid off 7,500 employees during the past year. Air Transat, significantly smaller than Canada 3000, cut 1,300 jobs. And, while domestic short-haul carrier WestJet announced another consecutive profitable quarter, Canada 3000 floundered, and, like Air Canada, it looked to the federal government for help. A generous precedent had been set by the United States, which offered a US$15 billion aid package, including both cash and loan guarantees, to its airlines. When Transportation Minister David Collenette announced the Canadian equivalent—$160 million meant to compensate the airlines for days lost due to closed airspace—airlines reeled again. At best, Canada 3000 would get $10 million, and according to its officers, it simply wasn’t enough.

“Canada 3000 was in Ottawa all the time at this point, going through hoops to get the little they would get,” says Koutoulakis. “And then they started to get into a queue—kind of take a number situation—to get more.” It was at this point that Lecky, Canada 3000’s chairman, made an astounding move. On October 15, he told reporters Canada 3000 would be out of money by Christmas unless the government came through with an adequate bail-out package. His statements took both the federal government and Canada 3000 by surprise—apparently Lecky acted independently without consultation with the airline’s president, Angus Kinnear, or other members of the board.

The immediate result was a seriously annoyed government and panicked creditors. As airport authorities in Canada and around the world retained lawyers and prepared to seize Canada 3000 aircraft, the Department of Transportation (informally) asked members of the Canadian Airports Council to hold off. Late in the evening of October 25, Collenette announced a $75 million loan guarantee for Canada 3000. Creditors breathed easier, and, for a few hours, it looked like Lecky’s gamble had paid off for Canada 3000. Then the airline saw the term sheet.

“I found it to be a fairly aggressive term sheet,” says Koutoulakis who, along with partner Renate Herbst, had the unenviable job of reporting on the terms of the loan guarantee to Canada 3000’s board of directors. “The conditions attached were unexpected from a government entity. It looked more like conditions I would expect to see in a capital venture deal or something like that, but not in a government assistance offer in the wake of 9/11.”

Canada 3000 officials said privately and publicly that the financial conditions were “severe and almost unworkable.” Although the term sheet is not in the public record, it is understood that the $75 million loan hinged on such conditions as demanding that investors inject $10 million in new capital, entitling the government to acquire one-sixth of the airline, and charging Canada 3000 an annual interest rate of 6 per cent in addition to the rate it would have to pay to a commercial bank. The real hurdle, however, proved to be the requirement to provide Ottawa with a viable business plan that showed a return to profitability. With passenger traffic falling off by 30 per cent, creditors clamouring for payment and the government bail-out fraught with conditions, Canada 3000 decided to take drastic action—eliminate the just-acquired Royal and the 1,500 people it employed.

The acquisitions of Royal and CanJet left Canada 3000 with numerous unions, collective agreements and differing levels of seniority and pecking orders, which it had been at some pains to integrate. William Phelps, Q.C., at Toronto-based Mathews, Dinsdale & Clark LLP, long-time labour advisor to the airline and negotiator of its first collective agreements, had spent several months working with the unions of CanJet, Royal and Canada 3000, attempting to integrate the employees into one body with streamlined union representation and collective agreements.

“There was a lot of work to sort this all out,” says Phelps, “and it was done successfully. Everyone involved would say so—there was no one party who won and others who lost. It was a good solution for everyone. I thought, great, we got that behind us.” The only task left was an appeal to the Canada Industrial Relations Board (CIRB) to restructure the three sets of unions representing pilots, flight attendants and other airline employees into one set. All the unions were on board. With that on his mind and a government loan guarantee in the background, Phelps flew his family, on Canada 3000, to Florida for a long overdue vacation. “The day after, I got a call telling me we may be in bankruptcy unless we can lay off a third of our employees.

“It all went back to the loan guarantees. To stay in business, we needed the loan guarantee. To get the loan guarantee, we had to have a viable business plan. To get a viable business plan, we needed to have staff reductions—we had to cut down the size of the airline by 30 per cent. The quickest and easiest way to do that was to separate Royal, which was still functioning as a virtually separate company, and end it.” For Phelps, this meant undoing the integration work of the summer, and asking the CIRB to permit Canada 3000 to treat Royal as a separate unit again. “All of a sudden, our position regarding the integration of the three airlines changed. We’re no longer going to integrate Royal, we now wanted to put it out of business…. Without a CIRB order, if we stopped Royal, Royal employees could bump Canada 3000 employees”—that is, laid-off pilots, flight attendants and other unionized employees with seniority could displace less senior personnel throughout Canada 3000 and the merged CanJet. The process would be disruptive, but, more importantly for Canada 3000, it would be expensive.

“Royal had the least suitable aircraft and was doing the type of flying that would have to go, in terms of the routes, the operating costs of the aircraft, the number of seats and so on,” explains Phelps. The difference in aircraft had huge implications for Canada 3000’s cost-cutting measures. “To train a Royal pilot to go from flying an Airbus 310 to a different aircraft, say an Airbus 329 or 320, would cost approximately $50,000 per pilot.” Multiply that by 150 Royal pilots, and “it was prohibitively expensive for a company already starved for cash.”

The CIRB process started on Monday, November 5. On Wednesday at noon, the CIRB ruled against Canada 3000, or rather, “The board said we’re not going to make this decision, you guys negotiate,” says Phelps. And negotiate they did, late into Wednesday night.

“We finally got agreements with the pilots. It was late, but it was not too late,” says Phelps. But it was not enough. Agreement with the Canadian Union of Public Employees (CUPE), the union representing the most employees at Royal, proved impossible. In Phelps’s opinion: “This is where CUPE has misled the press. They said they agreed to 500 layoffs. Yes, they did. But they wanted a guarantee that there would be no more layoffs, and how could the company guarantee that in the present climate? And they would not agree that these people be laid off until they were cross-trained, which would take four to six weeks, as any cross-training program would have to be government approved. And the company simply did not have that kind of time.”

According to Phelps, “That’s what really took it down. Otherwise, we would have had the documentation on the government’s table by Thursday morning. I’m told we would have had the loan guarantees, and we could have continued.”

Michael Church at Caley & Wray, who is representing CUPE in the current bankruptcy proceedings, believes that although “the union would not agree to [laying off all Royal employees], it would not have saved Canada 3000 anyway.” The company was in bad shape before September 11, he says, and those events only made a bad situation worse. Moreover, according to their lawyers, the unions never did know how bad things really were.

“The first day in court before Justice Ground, one of the union lawyers came up to me and asked, ‘Is Canada 3000 really in trouble?’” recalls Koutoulakis. “We’re in court filing for bankruptcy protection—what do you think?” was the reply.

“I was surprised by the speed with which the company went under and the magnitude of the company’s problems,” says Church. “Whoever was responsible did a good job of keeping things under wraps. I’m not blaming them—once people know, they’ll stop booking. Employees would have known in normal course, but in this case, did not. With the benefit of hindsight, the company should have come to the unions sooner and been more frank. The government never did come to the unions, and by the time the company came to the unions, it was basically over.”

According to Phelps, the unions had the facts. Some of them just chose not to believe them. “We had been telling them that for 18 hours. We told them we’d be in bankruptcy court on Thursday, and they told us not to make threats. ‘Don’t try to push us into a fast decision,’ they said. I said, ‘We’re not going to push you, the bankruptcy court is.’”

The proposal by the former owner of Royal to buy back the airline—at $25 million—threw a wrench into the negotiation process. “Leblanc fired over an offer letter, but to my knowledge, it was not considered and no one negotiated with him at all. His offer was highly conditional and was dismissed for a number of factors,” explains Koutoulakis. “Among the conditions was a government loan guarantee [for $30 million]…the board looked at it and felt it was so highly conditional as to not even be an offer. We were pretty annoyed.”

Leblanc’s “red herring” aside, the dire financial position of the company, says Phelps, “was certainly communicated to [the unions] under oath by the president of the company.… I told them myself about three times that night. CUPE thought we were bluffing.”

“They were very frank at the end,” admits Church. Unfortunately, by then it was too late. Canada 3000 walked away from the table frustrated and disheartened. It proceeded to apply for CCAA protection on Thursday, but without the union concessions needed to shut down Royal—the company had explored no other options—the $75 million loan guarantee was moving farther out of its reach. A press release issued at 5 p.m. that night—without the approval of Kinnear—informed customers that CCAA protection was granted, and the company would continue to operate. But that night, everything changed, and by Friday morning, Canada 3000’s airplanes were not flying.

“We were retained by Deloitte & Touche on Thursday morning, reviewed the order at lunch, and went to court that afternoon to get CCAA protection,” recalls Andrew Kent. “On Friday morning, the airline had shut down. On our advice, Deloitte & Touche filed a material changes report and Canada 3000 asked for time, over the weekend, to sort out what it was going to do. By Saturday, it looked like the company’s board was in the process of resigning.” Saturday and Sunday found the team at Deloitte & Touche, led by Kurt Bonokoski, and the team at McMillan Binch desperately trying to put together a bankruptcy.

“To put a company into voluntary bankruptcy, you need to have a resolution by the board of directors. There was no board. A hostile bankruptcy needs to be initiated by a creditor—there was no creditor initiating that,” explains Kent. Pressed for time, Mr. Justice Ground approved an option put forward by McMillan Binch and Deloitte & Touche “giving the monitor the authority to put the company into voluntary bankruptcy.” The monitor then had to find an official receiver to accept a bankruptcy assignment on Sunday evening. By Monday, November 12, two-and-a-half weeks after Collenette’s not-so-guaranteed loan guarantee, a week and a half since Tango’s first flight, four days after negotiations with CUPE failed, and two months after 9/11, Canada had one less airline in its skies. It would take some time before Canadians—including the Transportation Minister and the Competition Bureau Commissioner—would accept this.

As Deloitte & Touche informed the court that despite the CCAA protection that stipulated the airline continue operations, Canada 3000 had grounded all its planes and Konrad von Finckenstein, Q.C., announced that the Competition Bureau was just about to put a cease and desist order on Air Canada’s Tango in response to Canada 3000’s October 12 complaint. “Sweet, eh?” comments Koutoulakis. “It was totally disheartening. Why are you saying this? You know this can’t help us—it can’t help anyone. I still can’t understand why they didn’t issue the cease and desist order. If it didn’t help Canada 3000, it could have helped some other people. The timing was incredulous.”

“The timing of the bureau’s announcement regarding Tango was unfortunate,” concurs Gordon Capern of Paliare Roland Rosenberg Rothstein LLP, representing the Greater Moncton Airport Authority. “All it did was demonstrate that the Competition Bureau cannot deal with these issues in a timely fashion. It was ironic.”

Fridhandler at Burnet, Duckworth & Palmer thinks that’s an understatement. “It was just garbage. Easy to say that after the fact,” especially when the end result was that the Competition Bureau didn’t do anything, as the affected party, having been permanently knocked out of the sky, was no longer being hurt. But, says Fridhandler, “Canada 3000 was on its way out anyway. Tango didn’t do it. It may have been the final nail in the coffin, but it didn’t do it.”

Koutoulakis doesn’t think Tango knifed Canada 3000 either. But Air Canada—that’s a different story. “Tango as Tango was only flying for a few days,” he says. “The big question is, was Air Canada a factor? Tango is just one and the latest arrow in their quiver.” And, although he sees Air Canada’s behaviour as “categorically” anti-competitive, his major beef is not with Air Canada. It is with the regulated but unenforced environment in which the game is played out.

“Would I call what they do anti-competitive in an open market? No,” says Koutoulakis. “Ruthless, but good business. As an MBA or a business person, do I think Tango is a good idea? How can you not? But if the federal government puts these rules, calls certain practices predatory behaviour—then yeah, it’s anti-competitive.”

Capern agrees that “Air Canada has demonstrated extreme anti-competitive behaviour.” And, most pertinently, “The Competition Bureau has been unable to deal with it for the last 10, 15 years.” WestJet’s director of public relations and communications Siobhan Vinish concurs, and calls for “a Competition Act with teeth to it to ensure competition.”

If the Competition Bureau is ineffective, the federal government can best be characterized as confused. Says Mario Forte at Ogilvy Renault, “Part of the problem was the government sticking its oar in the water. It created a false impression.” Lawson Hunter, Q.C., formerly a commissioner of the Competition Bureau and presently senior competition counsel with the Air Canada team at Stikeman Elliott, believes the federal government should never have gotten involved in the aviation industry in the first place. “They got involved once,” he says, “and now they feel they have to keep on doing something.” Unfortunately, it frequently appears that they have no idea what that something is.

The precedent of meddling creates certain expectations. “I thought there was going to be some financing by the government,” admits David Kee of Blake, Cassels & Graydon LLP in Toronto, who is representing Royal creditor CIBC. Given the government’s past behaviour in respect of Hunter’s client, the expectation was not unusual. Says Capern, “Not to say that Canada 3000 was not the author of its own misfortune, but it seems that Air Canada can make one mistake after another [and it gets bailed out], but every other airline makes one management mistake and it pays immediately.”

As Collenette finally came to terms with the fact that Canada 3000 would not fly again, he assured Canadians that the federal government “absolutely did as much as we could.”

Perhaps it did. Phelps doesn’t have any issues with the conditions attached to the not-so-guaranteed loan guarantee. His issue is with the unions—or, more specifically, “Two or three very militant, vocal people at CUPE pushing their opinions on everyone. They led the bargaining committee astray” and effectively hijacked the proceedings. “I have great trouble understanding the logic of, ‘We’re going to refuse to make concessions to the employer to keep the employer alive even if it takes the airline down.’ Are you better off with 10 to 20 per cent of your people out of work for two months or everyone out of work permanently?” In addition to representing flight attendants at Canada 3000, CanJet and Royal, CUPE is also the bargaining agent for flight attendants at Air Canada. And that raises an interesting question.

“Whether they did not believe us or whether they were afraid if they agreed to this with Canada 3000, they might have set a precedent for Air Canada, who they also represent, I don’t know,” says Phelps. But if they did, “they effectively sacrificed the Canada 3000 people for the Air Canada people.”

So, bushwhacked or reckless? Who is to blame? Unreasonable unions, a federal government ineptly playing business hardball, a well-meaning but ineffectual Competition Bureau, a ruthlessly anti-competitive Air Canada, a softening economy, or 9/11? Daryl Fridhandler is blunt: “They did it to themselves.” And, as Capern puts it, it is hard not to see Canada 3000 as the author of its own misfortune.

While its directors could not have predicted 9/11, it is hard to see the acquisition of Royal as a prudent move—particularly as Canada 3000’s August Statement of Claim against Royal makes clear, there were concerns about the acquisition’s finances and disclosures throughout the negotiations. The apparent lack of communication between Lecky and Kinnear, demonstrated by Lecky’s revelations about the company’s financial status on October 15, and subsequent (mis)communication of events during the company’s weekend of crisis, must have had an effect on the strategic efficacy of the company. Lecky’s October 15 statements may have been intended as a spur to the federal government; but their first and most lasting result was to jitter creditors, domestic and international. The calls for cash could be staved off for a while with assurances that a government bail-out was coming, but most airport authorities weren’t willing to take that chance. And, as Lawson Hunter, with massive understatement, deadpans “Once people start seizing planes, it’s over.”

The end for Canada 3000 meant the beginning of a long and protracted process for its many creditors and lessors, jockeying for a piece of whatever remained. And the process is not a happy one. “I hate it,” says Forte. “If you find anybody who says otherwise, they’re lying. There are no happy faces on this file.”

One of the first and most positive accomplishments of the creditors was getting pay cheques to Canada 3000’s employees. Says McMillan Binch’s Neil Saxe, “There was every intention [on Canada 3000’s part] to pay its employees. Everyone had that expectation. It seemed the right thing to do, to get these people their last pay cheque. We worked with everyone, and everyone co-operated.” The company had about $20 million in a Royal Bank of Canada account and RBC, one of the few secured creditors in the matter, “was willing to take the risk.” On November 22, with the full co-operation of RBC and other creditors, the Ontario Superior Court of Justice released $6.3 million from the account for payment of back wages to the airline’s 4,800 employees.

“It was an unusual thing, but right thing to do,” says Kent. And, while some creditors may have had private reservations about releasing that much money so early in the process, “No one was prepared to say ‘no,’ publicly.”

The court order was good news for Canada 3000 employees, but potentially bad news for its ex-directors. “When the court authorized the employees to be paid, it reserved the right for them to seek redress,” explains Kent. In other words, “Directors still have some personal liability.” And the mystery of the en masse November 10 resignation, Kent believes, is best understood as “a fundamental conflict between operations and liability.”

“In this case it’s clear that the resignations were motivated by a concern regarding personal liability. The company had about $20 million in the bank…. It was losing cash daily, and the directors didn’t want to see the money spent,” says Kent. Continuing operations meant continuing to spend money, and the less money Canada 3000 had when the end finally came—as seemed inevitable by the first week of November—the more personal liability its directors would have. The rapid dissolution of the board was their inelegant solution, the efficacy of which is still to be tested in the courts.

Once the employees received their last pay stub—severance, termination, benefits and other employee claims remain outstanding—Deloitte & Touche decided to step aside as trustee in bankruptcy. It had been filling the peculiar dual role of monitor under the CCAA and trustee in the bankruptcy since the crisis weekend. On November 16, as the remainder of Canada 3000 subsidiaries, including Canada 3000 Holidays, Canada 3000 Tickets and Royal Handling Inc. made assignments in bankruptcy, PwC came into play as their trustee in bankruptcy. On November 30, the court approved Deloitte & Touche’s request that it be replaced as trustee by PwC.

“Under the statute, if you’ve been an auditor of a firm within two years, you should not be its trustee in bankruptcy,” explains Neil Saxe. “There’s a specific provision in the CCAA that you can be a monitor even if you were an auditor.” When Canada 3000’s CCAA protection turned into a bankruptcy, “There was nobody in charge of the assets. Deloitte & Touche was there, and it made sense for Deloitte & Touche to fill the role of trustee.” The bankruptcy statute does provide for such a case, with the court’s approval. And the court was pleased to approve. “But Deloitte & Touche was still concerned about its position according to its own professional standards.” It stepped down, and PwC, under the leadership of Karen Cramm, took over. McMillan Binch remained as legal advisor through the change of trustees, providing continuity.

Continuity was sorely needed, as the “priority dispute” among the major creditors came into full swing. The first set of battle lines was drawn between owners of aircraft leased to Canada 3000 and the airport authorities and NAV Canada. The burning issue—who has rights to the planes? The immediate issue—what to do with Canada 3000’s 42 aircraft, which, although grounded, needed ongoing maintenance and care?

“The first skirmish was to release the aircraft,” says Michael Rotsztain at Torys LLP, representing US Airways, which leased 11 airplanes to Canada 3000. “There’s a fair amount of solidarity among the lessors,” whose right to their aircraft is contested by NAV Canada and the airport authorities. “NAV Canada and the airport authorities, to varying degrees, claim that they were victims of timing, that the CCAA filing froze their rights to apply for seizure,” explains Rotsztain. But before the main engagement between the two parties would settle this issue, the lessors wanted to get their planes back, re-lease them if possible, and thus not compound their losses. In short, says Michael Feldman also at Torys, who is working with lessors US Airways, International Lease Finance Corporation and Aviation Capital Group, “These are our aircraft and we want them back.”

Mr. Justice Ground obliged, and as the lessors posted securities, bonds and letters of credit—in case NAV Canada and the other parties were successful in subsequent litigation—planes were gradually released and re-leased. But the main event, which would establish whether NAV Canada and the airport authorities did indeed have seizure rights to lessors’ aircraft, was just starting in late December.

“Our position is that NAV Canada is a secured creditor because of the seizure rights,” explains Fournier at Gowlings. “Section 55 [of the Civil Air Navigation Service Commercialization Act, CANSCA] makes the owner and operator for aircraft jointly liable. Section 56 gives to NAV Canada the right to seize aircraft in respect of which charges have arisen.” These rights, says Fournier, apply to any aircraft owned and operated by the person owing money, not just the specific aircraft to which the charges apply. “The lessors are saying they are not owners as defined in this Act and therefore not liable to make payment. That issue has arisen in the InterContinental case in Quebec.” In that airline bankruptcy case, the Quebec Superior Court found in favour of the position taken now by NAV Canada. The case, however, is under appeal and is unlikely to be resolved before a decision on the Canada 3000 case is made. “Laws will be formed by this case,” says Fournier.

From the opposite side, Rotsztain agrees. “It’s an important case for the airline industry. What kind of country is Canada if you are just a lessor and you find yourself subject for navigation fees, airport charges, etc.? You have no way to protect yourself.”

“The decision of the lower courts will not be final,” predicts Fournier. “There will be appeals.”

In other words, as Forte says, “We may all be getting old on this.”

While NAV Canada and the lessors duke it out, other creditors are taking a back seat. “We’re taking a low profile because our assets in Royal are not substantial,” Kee explains CIBC’s position.

AMEX Bank of Canada, represented by Deborah Glendinning from Osler, Hoskin & Harcourt LLP, is likewise “just monitoring what is happening.”

The trustee, too, whose job it is “not to take sides, but to make sure things are done right,” is watching from the sidelines. McMillan Binch’s lead litigator on the file, Daniel MacDonald “is trying to stay out of it as much as possible, because it’s a real cat fight right now,” says Kent.

The cat fight is now taking place solely under the auspices of the bankruptcy proceedings. The CCAA protection was terminated on December 7. “It was useful while it was there, because it provided stability, kept people from grabbing things, and kept open the possibility of reorganization,” says Kent. “But it became clear to the monitor from the proposals offered that we’d be looking at a sale of pieces, not a reorganization of the whole.”

A number of interested parties, including Kinnear and Leblanc, have approached the monitor, the trustee and the unions with tentative proposals. The group working with Deloitte & Touche, which is said to include former Canada 3000 executives and investors, is considering leasing 10 Airbus A320s and possibly using the Canada 3000 name. Deloitte & Touche’s Michael Badham has been quoted in the national press as saying, “Our own sense is there’s a lot of value in the Canada 3000 name. It is associated with reliable, affordable service.” Needless to say, there are 50,000 Canadians who were stranded around the globe in mid-September of last year who may disagree with Mr. Badham.

However, before a phoenix rises from Canada 3000’s ashes, potential investors have one concern: “What is the government’s policy going to be vis-à-vis Air Canada?” asks Kent. “If it’s fine for Air Canada to use a Tango or another ‘fighting brand’, what’s the point of investing? There’s a plan and a willingness to finance that plan right now, but the key point is, what is the government’s policy?”

In the wake of this and other uncertainties, Koutoulakis is very cautious about any future Canada 3000 phoenixes. “Air Canada’s still out there, we still have the recession, the dollar still sucks. Anyone who starts an airline right now—what can I say, God bless.”

For now, as the aviation industry shakedown continues, the federal government ponders its next tremulous step, and potential investors bide their time, Canadian consumers have less choice and more worry.

“We’re at the mercy of Air Canada,” says Phelps. And like Canada 3000, Air Canada is at the mercy of a confused federal government, a heavily unionized labour force, and free market economic forces with which it appears unable to cope.

Says Fridhandler, “Someone’s got to be keeping an eye on their cash reserves. I’m sure taxpayers of this country won’t want to bail them out.”

Should the national carrier ever require an obituary, it could not aspire higher than to the last words said about Canada 3000 by competitor WestJet. Eulogizes Vinish, “Canada 3000 was a good airline. It provided good service. The marketplace will miss it.” Amen. We await with anticipation for whatever may arise from its ashes.

Marzena Czarnecka is a Lexpert staff writer.

Lawyer(s)

Andrew J.F. Kent

Christopher A. Fournier

Mario J. Forte

Daryl S. Fridhandler

Tom Koutoulakis

Renate D. Herbst

W. G. Phelps

Michael A. Church

Kurt P. Bonokoski

Gordon D. Capern

Siobhan Vinish

Lawson A.W. Hunter

William J. Burden

John N. Birch

Karen Cramm

Clifton P. Prophet

Alan Butcher

Robin D. Walker

Eric Wredenhagen

Donald C. Ross

Lyndon A.J. Barnes

Donald D. Hanna

Fred Myers

Arthur J. Peltomaa

Marcus A. R. Knapp

David Chernos

Marc Lavigne

Scott A. Bomhof

Richard A. Conway

Melissa T.G. LaFlair

Elizabeth J. Evans

James J. Feehely

Deborah A. Glendinning

Daniel V. MacDonald

David A. Allen

Firm(s)

McMillan LLP

Deloitte LLP

PwC Canada

NAV CANADA

Gowling WLG

Gowling WLG

Norton Rose Fulbright Canada LLP

WestJet Airlines

Burnet, Duckworth & Palmer LLP

Cassels Brock & Blackwell LLP

Royal Aviation Inc.

Sun Life Assurance Company of Canada

McCarthy Tétrault LLP

Mathews, Dinsdale & Clark LLP

Canada Industrial Relations Board

Canadian Union of Public Employees (CUPE)

CaleyWray

Paliare Roland Rosenberg Rothstein LLP

Blake, Cassels & Graydon LLP

CIBC

Royal Bank of Canada

US Airways Group, Inc.

International Lease Finance Corporation

Aviation Capital Group

Osler, Hoskin & Harcourt LLP

Amex Bank of Canada / Amex Canada Inc.

Borden Ladner Gervais LLP (BLG)

Borden Ladner Gervais LLP (BLG)

General Electric Capital Canada Inc.

Pegasus Aviation, Inc.

Wells Fargo Financial Canada Corporation

LBC Capital

Ansett Worldwide

Thornton Grout Finnigan LLP