As the “critical metals” race grows, there will be an increasing focus on geopolitical risks. The drive to find and develop mines in stable jurisdictions such as Canada will also ramp up, say lawyers experienced in mining law.

Climate change and the focus on ESG concerns have prompted a massive focus on base metals such as copper and critical minerals such as lithium to keep up with the demand for electric cars. Likewise, fewer large deposits of precious metals such as gold and silver are found in “safe” regions such as Canada, the United States, and Australia, which means navigating the production pipeline in countries where the rule of law and other geopolitical risks are a concern.

Canadian mining companies still see opportunities abroad. Indeed, Canada is home to almost half of the world’s publicly listed mining and mineral exploration companies, according to Statistics Canada. About 1350 of these companies in Canada had assets valued at $273.4 billion in 2020, a 3.7-percent increase from $263.6 billion in 2019.

Of these companies, 730 had assets located abroad worth $188.2 billion, up 4.3 percent in 2019 and accounting for about two-thirds of the total. Canadian companies were present in 97 foreign countries in 2020, down from 99 the previous year, with these assets abroad accounting for about two-thirds of the total value of CMAs.

“Companies like to be in stable jurisdictions, but there is a shrinking pipeline of those,” says Amanda Linett, head of the mining group of Stikeman Elliott LLP. “So, there may be an appetite for greater risk when it comes to metals like copper and nickel.” However, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine highlights the importance of geographic diversity in assets and how regional instability can disrupt supply chains.

The push for critical minerals

The need for raw materials in managing this transition presents a considerable challenge. Decarbonization efforts, ironically, will require more mining. Electric vehicle manufacturing requires, on average, six times the amount of minerals such as copper, cobalt, and lithium than it does to build gas-powered cars.

According to analyst firm Wood Mackenzie, global production of aluminum, copper, zinc, and high-grade nickel must increase fivefold by 2040. And the World Economic Forum expects the production of minerals like lithium, graphite, and cobalt to increase fivefold by 2050 to meet the demand for clean-energy technologies.

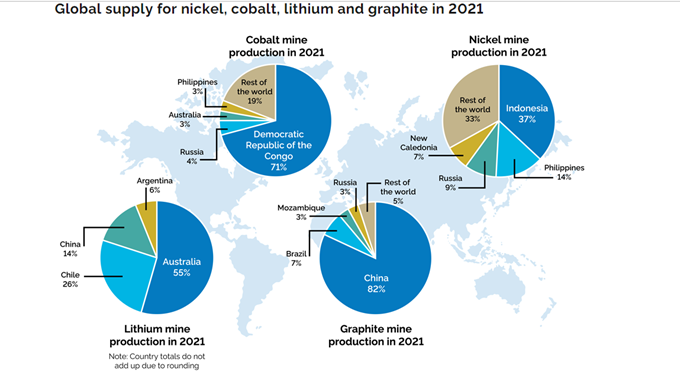

But the supply side shows many of the potential geopolitical risks that mining companies are facing these days in looking for and mining these metals:

About 85 percent of the world’s neodymium, a rare earth metal crucial for products such as motors, turbines, and medical devices, is concentrated in a few Chinese mines.

China also has the market on three of the five minerals needed for photovoltaic cells – 73 percent of known gallium reserve, 67 percent of germanium, and 57 percent of indium.

Most of the world’s cobalt production comes from the politically unstable Democratic Republic of Congo, which has about 65 percent of the world’s known cobalt reserves, an element critical for extending the longevity of electric vehicle batteries.

A large share of palladium, used in catalytic converters, is mined in Russia, which is subject to Western sanctions after it invaded Ukraine.

About 20 percent of high-grade nickel, a crucial ingredient of electric-vehicle batteries and stainless steel, comes from Russia.

Refining and manufacturing capacity figures for these “green” minerals also show that some countries, like China, are ahead of the game. The Economist reports that China refines 70 percent of the world’s lithium, 84 percent of its nickel, and 85 percent of its cobalt, controlling about 80 percent of global battery cell-manufacturing capacity.

The geopolitics of “green” mining

International trade is necessary to meet the global mineral demands of the energy transition, but geopolitics could interfere. Even countries that have long been considered friendly for mining investment have taken steps to protect their resources, the environment, and profits from the explosion of interest in lithium.

Mexico, for example, nationalized its lithium resources earlier this year, though President Andrés Manuel López Obrador urges the private sector to work with his new state-run lithium company.

“We wouldn’t have enough for it to be only public. It requires a lot of investment,” López Obrador has said.

The government expects the state miner named Litio para México, or Lithium for Mexico, to launch within months, but has given few details on how it will operate. Mexico does not yet have commercial lithium production, though about a dozen foreign companies hold contracts to explore potential deposits.

Bolivia is also proposing joint ventures to extract lithium under a system with the nation owning 51 percent of the entity and taking around half the profits. To do that, it first needs to amend Bolivian law, which does not allow foreign firms to extract lithium. Local government officials are using that as an opportunity to lobby for their share of the royalties, threatening to take to the streets as they did in 2019 when community anger killed off a Bolivian partnership with German firm ACI Systems to develop lithium batteries.

President Pedro Castillo unnerved the mining industry in Peru when he won a narrow election in 2021 by appealing to the working class, especially those in or affected by mining. Since then, social and political conflicts have been affecting the mining sector in Peru, the second-largest copper producer in the world (after Chile). This type of uncertainty could put the brakes on mining investments and projects.

And Chile, home to more than 50 Canadian mining companies that represent about 10 percent of Canada’s international mining assets, recently voted in a left-leaning government that had hoped to change the country’s constitution to strengthen environmental regulations and indigenous rights over mining. However, that change was defeated in a referendum held in September.

Article 145 of the proposed constitution, for example, would establish the state’s absolute domain over “all mines and mineral substances, metallic, non-metallic and deposits of fossil substances and existing hydrocarbons in the national territory.” It adds that “the exploration, exploitation and use of these substances will be subject to a regulation that considers their finite, non-renewable nature, intergenerational public interest, and environmental protection.”

Canada’s place in the critical mineral supply chain

According to the United States Geological Survey, last year, Canada produced five percent of the world’s nickel, 2.8 percent of copper, 2.5 percent of cobalt, and one percent of the world’s supply of graphite. While the search for critical minerals in Canada is ongoing, it does not produce any lithium or rare earth elements, though Canada does have untapped reserves of both.

Leanne Krawchuk, a partner with Dentons Canada LLP and the Canada co-chair and global lead for Dentons’ mining group, says that Canada’s 2021 critical-minerals strategy has prioritized 31 minerals. These include cobalt, coltan, copper, graphite, lithium, and rare earth elements. Canada lacks mines producing several of these minerals.

“We need a tremendous acceleration of investment in critical minerals in Canada,” says Krawchuk. “The good news is that we see global demand increasing, the pricing getting higher, which helps with the feasibility of taking a mine to profitable production.”

She points out that similar economics apply as prices rise for precious metals like gold and silver. “Do we now have a chance to go back to reserves still in the ground and look at whether we go further down or use technology to find high-demand assets?”

Sander Grieve practises public market finance and mergers and acquisitions at Bennett Jones LLP, focusing on global mining exploration, development, and extraction. He says that Canada, along with the United States and Australia, is a desirable country for finding and producing both critical minerals and precious metals.

However, he notes that Canadian public policy must keep an eye on “remaining competitive” in attracting mining investment. “Australia would love to have that investment, and the US has become a more competitive jurisdiction,” he says. He adds that even state laws can make a difference in the US – Nevada is much friendlier to mining than California.

To that end, the federal budget earlier this year allocated up to $3.8 billion to invest in responsible mineral processing and recycling, expand exploration, and provide tax credits for critical-mineral exploration, along with providing tax credits for critical-mineral exploration.

The federal Ministry of Natural Resources says Canada has some of the world’s largest known reserves and resources of rare earth elements, estimated at 14 million tonnes of rare earth oxides in 2021. A rare-earth demonstration mine also opened in 2021, the second such pilot in Canada.

Grieve says that, in the wake of some of the geopolitical risks to mining in other jurisdictions, Canada needs policies focusing on the domestic mining of these critical minerals. “We’ve seen various governments renegotiating mining tenements, cancelling ownership rights in various parts of the world, nationalizing certain areas of mining,” he says.

“That doesn’t happen here, but regulations and the permitting process can sometimes lead to the same result – we need to be sure we’re attracting investment and not turning off potential investors.”

Source: Ontario’s Critical Minerals Strategy 2022–2027 report