Pursuant to its jurisdiction over monetary policy, the Bank of Canada (“BOC”) implemented seven interest rate hikes in 2022, increasing interest rates from 0.25% to 4.25%.[1] These interest rate increases have been criticized by economists, politicians, and the public alike. Still, the BOC remains steadfast, arguing that these drastic increases are necessary to control inflation.[2] This article will explain the history of inflation in Canada and the reasoning behind the BOC’s aggressive interest rate increases, evaluate the current criticisms against the BOC, and analyze several potential solutions to Canada’s inflation problem.

The BOC’s recent interest rate hikes

In early 2021, inflation in Canada began rapidly increasing, reaching a four-decade high of 8.1% by June 2022.[3] In response, the BOC halted quantitative easing (the purchasing of government bonds by the central bank to stimulate economic growth) and began increasing interest rates.

Why has inflation increased?

When the COVID-19 pandemic began in 2020, the Canadian markets crashed. Unemployment rates skyrocketed. The economy fell into a severe recession.[4] In response, the BOC took action to stimulate the economy by slashing interest rates and purchasing massive amounts of government bonds.[5] These actions proved successful -- perhaps too successful -- as by early 2021, the Canadian economy had almost completely recovered.[6]

Recent Articles

The economic stimulus from the BOC’s monetary policies paired with government monetary aid resulted in an estimated $100 billion waiting to be spent by consumers by early 2021. When lockdowns lifted, this pent-up demand quickly exceeded supply, resulting in an increase in prices and inflation. This supply and demand imbalance was further exacerbated by supply chain issues, stemming from lockdowns in high-manufacturing countries, like China.[7] Making matters worse, in February 2022, Russia invaded Ukraine, causing the prices of oil and agricultural products to rise globally.[8] It is thought that the combination of these factors resulted in rapidly increasing inflation in 2021 and 2022.

How did the BOC respond to inflation?

When inflation increased in early 2021, the BOC believed that it was transitory, caused by a temporary post-pandemic imbalance between supply and demand.[9] The BOC indicated that they would keep interest rates low until at least early 2023 and forecasted that inflation would return to 2% by the end of 2022.[10] The BOC maintained this position throughout 2021, even as inflation reached 4.8% in December 2021.[11]

Contrary to the BOC’s forecast, inflation continued to increase, showing no signs of stopping. In January 2022, inflation reached 5.1%[12] and the BOC finally reversed their position and announced that they would end quantitative easing and begin to increase interest rates.[13] The BOC acknowledged that current inflation was not transitory and monetary policy was required to control it. Following their January 2022 announcement, the BOC increased interest rates seven times, bringing rates from 0.25% in January 2021 to 4.25% in December 2022.[14]

How does increasing interest rates help control inflation?

Higher interest rates make borrowing more expensive for both consumers and businesses, resulting in reduced spending and demand.[15] Reducing demand alleviates supply and demand imbalances, which reduces prices and ultimately, inflation.

Why is the BOC so concerned about inflation?

Inflation is not inherently harmful. In fact, a low and steady level of inflation is encouraged in developed economies as it signals a growing economy.[16] However, inflation that is too low or too high is generally detrimental.

A lack of inflation, where prices are decreasing, is referred to as deflation. Deflation is undesirable because it causes consumers to delay making purchases since they expect prices to continue to fall. [17] This results in less economic activity and no economic growth.

High and volatile inflation is equally undesirable as it creates uncertainty. Uncertainty in an economy encourages speculation and pricing bubbles, as consumers are unable to make sound economic decisions.[18] In addition, high inflation disproportionately affects low- and fixed-income individuals, as such individuals rapidly lose purchasing power with little to no recourse.[19] Moreover, high inflation presents an additional danger of entrenched inflation expectations. If inflation begins to increase and consumers have little faith in the BOC’s ability to control it, consumers will choose to make purchases quickly in fear of prices increasing. This results in increased demand, which further increases inflation by creating a supply and demand imbalance. Therefore, high and volatile inflation creates the risk of a self-perpetuating cycle, where the high and volatile inflation results in entrenched inflation expectations, which further increases inflation, which further entrenches inflation expectations.[20] In controlling inflation, the BOC must strike a delicate balance between stimulating the economy while avoiding excess inflation.

Why is the BOC acting so quickly and drastically?

Historically, periods of sustained high inflation are often followed by severe recessions.[21] For example, in the 1970s and 1980s, Canada experienced two decades of high inflation, with inflation in the double digits for many years.[22] The BOC was unable to control inflation for two decades and when inflation was finally reduced in 1991, the Canadian economy entered into a severe recession.[23]

One factor that contributed to the inflation crisis in the 1970s and 1980s was the public’s entrenched inflation expectations. During this period, the BOC did not have an explicit inflation goal and the public did not believe that the BOC could successfully control it. As above, the public’s expectations of high inflation created a self-perpetuating cycle, and the BOC was unable to reduce inflation despite increasing interest rates to over 10%.[24] It was not until 1991, when the BOC adopted an explicit 2% inflation goal and made clear policy announcements that quantitative tightening would not end until inflation was controlled, that inflation was finally reduced. Learning from this era, the BOC has paired their recent interest rate increases with clear policy announcements that quantitative tightening will continue until inflation is controlled.[25]

Are the recent inflation rates really that bad?

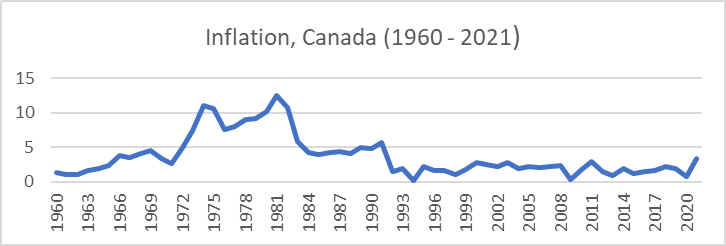

The following chart shows inflation in Canada from 1960-2021.[26]

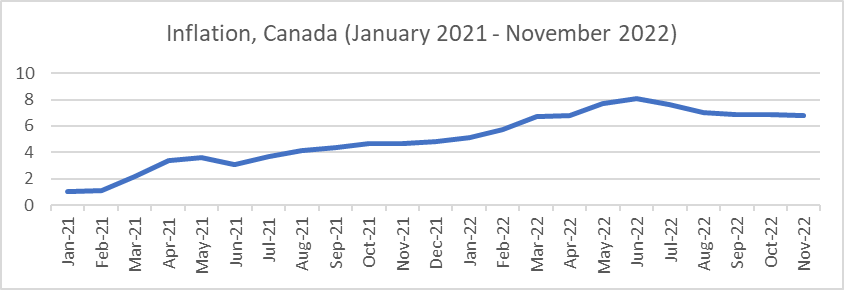

The next chart provides a closer look at recent inflation rates, displaying inflation from January 2021 to November 2022.[27]

Referring to the above graphs, current inflation is not the most severe inflation that Canada has experienced. Canada’s worst period of inflation was from 1971-1990, with inflation peaking at 12.5% in 1981. However, current inflation is the highest it has been since that time. In addition, the trajectory of inflation in March 2021 was dangerously starting to mirror inflation in 1971.[28] Therefore, although current inflation is not the highest in Canadian history, the BOC is rightfully concerned given the high numbers and alarming trend.

What’s different about current inflation compared to the past?

Although current inflation is not at a historical high, several unique macroeconomic factors have created circumstances that may worsen inflation past 1980 levels. These unique circumstances include globalization and the current near-record low unemployment rates.

Compared to the 1980s, the current Canadian economy is much more sensitive to global events due to globalization.[29] These events, like Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, often cannot be predicted or controlled by the BOC. This means that even if the BOC is successful in controlling domestic demand and monetary supply, domestic inflation rates remain susceptible to external shocks.[30]

Next, current unemployment rates are starkly different from unemployment rates in the 1980s. During the periods of peak inflation in the early 1980s, unemployment rates soared and reached over 12%.[31] Recent unemployment rates show the opposite trend, as despite increasing inflation, unemployment rates have steadily decreased since January 2021, to a near record low of 4.6% in November 2022.[32] While low unemployment rates are typically positive, this is not the case for Canada. Currently, Canada’s low unemployment rates aren’t caused by economic growth, rather they are thought to be the result of a declining workforce and low birth rates.[33] A declining workforce usually translates into a decline in economic production and output, resulting in persistent supply chain issues and aggregate demand continuing to outstrip supply.[34] As a result, prices may continue to rise, and inflation may persist.

Therefore, although recent data suggests that inflation is slowing, several unique challenges in our current economic environment means that the BOC may need to take more drastic measures to fully control inflation.

Canada vs. the US and UK

While all three central banks in Canada, the US, and the UK have increased interest rates, the BOC has moved faster and more aggressively than the Federal Reserve and Bank of England. As of December 2022, interest rates in Canada stood at 4.25%, while the US and UK had interest rates of 4% and 3%, respectively.[35] Due to the BOC’s actions, Canadian inflation rates are lower than in the UK and US and the Canadian economy appears to be in better shape.[36]

Therefore, despite recent criticisms of the BOC, compared to other developed economies and historical trends, the Canadian economy and inflation rates have fared relatively well.

Why is the BOC under attack?

With rising inflation and interest rates, the BOC and BOC governor, Tiff Macklem, have become the centre of criticism by politicians, economists, and the public.

One criticism against the BOC accuses it of ignoring the early warning signs of inflation and acting too late to address it. By early 2021, many economists speculated that inflation would increase sharply due to pent-up demand and warned that if the BOC did not halt quantitative easing, the economy would face high and sustained inflation.[37] The BOC opposed these views as it believed inflation was simply transitory and continued keeping interest rates low.[38] The BOC held this position in the face of increasing inflation and did not act to control inflation until January 2022.[39] Critics of the BOC’s policies claim that by ignoring the early warning signs and failing to act quickly, the BOC not only allowed inflation to become a problem, it actively contributed towards that problem.[40]

The BOC responded inappropriately to the pandemic and current inflation

A second attack on the BOC involves criticisms towards the BOC’s response to the 2020 recession. Critics argue that by summer 2020, it was clear that the economic damage from the pandemic was contained to industries that required face-to-face contact.[41] Therefore, the BOC should have halted economy-wide stimulus and instead focused on implementing targeted support programs to the industries affected by the pandemic.[42] By failing to do this, the BOC overstimulated the economy and caused inflation. In addition, some critics further argue that the BOC’s current response to inflation is inappropriate as hiking rates too quickly may result in another severe recession.[43]

Macklem’s statements about interest rates

A third attack against the BOC is directed towards statements made by Macklem. In a July 2020 press conference Macklem made statements encouraging Canadians to make major purchases, like housing, because the BOC would keep interest rates low “for a long time.”[44] Critics of the BOC claim that these statements misled Canadians into believing that inflation would not be a problem and interest rates would remain at near zero for the foreseeable future.[45] By making these statements, the BOC increased demand and as a result, increased prices, particularly in the housing market where intense demand caused average housing prices in Canada to increase more than 50% from April 2020 to February 2022.[46] This spike in housing prices contributed to rising inflation. In addition, many recent homeowners took variable mortgages after Macklem’s statement. These homeowners blame the BOC for misrepresenting that interest rates would not increase until at least 2023, and for their substantial increases in mortgage payments due to the interest rate hikes.[47]

Reforms to the BOC

Along with attacks and criticisms, there have been calls to reform, and even abolish, the BOC.

Replacing the BOC with cryptocurrency

Calls to abolish the BOC and replace our central bank with cryptocurrency have been led by conservative leadership candidate Pierre Poilievre.[48] Replacing the BOC with cryptocurrency would mean that no one, including the BOC, would have control over the money supply. Initial proponents of this proposal claimed that cryptocurrency is an inflation-safe asset that would not be affected by macroeconomic factors.[49] In the early days of the pandemic, this seemed like an alluring option as cryptocurrency prices skyrocketed, with Bitcoin trading at $68,000 and the cryptocurrency market reaching an estimated worth of $3 trillion.[50] However, this was quickly proven to be an ill-advised proposal when the cryptocurrency market crashed in 2022, with bitcoin falling to under $20,000 and the cryptocurrency market falling to under $1 trillion.[51] Clearly, cryptocurrency is not insulated from inflation or macroeconomic factors and would be a poor choice to replace the BOC.

Replacing Macklem

Alongside his calls to abolish the BOC, Poilievre has also called for the replacement of Macklem. Poilievre accuses Macklem of making policy decisions based on political pressures and being a “cash-cow” to the Trudeau government.[52] Similar to Poilievre’s first suggestion, this proposal is ill-advised. First, removing the governor is not provided for in the Bank of Canada Act.[53] Therefore, replacing the governor before his term ends would require the creation or amendment of legislation.[54] Next, this suggestion has been criticized from individuals from all political parties, including other conservative politicians.[55] Much of the criticism recognizes the importance of the independence of the BOC from political and executive pressures. The BOC often makes politically unpopular decisions for the betterment of the overall economy. Therefore, allowing or making unsubstantiated threats towards the BOC’s independence would prevent the BOC from making effective and non-partisan policy decisions.[56]

Central bank digital currency

Although most central banks are opposed to cryptocurrency replacing central banking, many central banks, including the BOC, are considering issuing a central bank digital currency.[57] Proponents of this idea claim that a central bank digital currency would allow central banks to implement more effective monetary policies. Traditional monetary policies often result in widespread effects on the economy that are hard to predict and measurable only in the aftermath.[58] Since digital currency is fully programmable, if the BOC were to create and adopt one, the BOC would be able to engage in micro-targeting within the economy. For example, digital currency could be programmed to only allow use in certain sectors, regions, socio-economic classes, or time periods.[59] It would also allow the BOC to set different interest rates on different balances or accounts. This would allow the BOC to implement more effective monetary policies by focusing on sectors that require stimulation, without overstimulating other sectors.[60] Furthermore, a second problem with modern monetary policy is the lagging effect. Currently, the effects of monetary policy cannot be seen until 18-24 months after implementation, creating the risk of overtightening or overstimulation of an economy.[61] Digital currency solves this problem by allowing for real-time feedback of economic effects. However, while the benefits of digital currency seem great, the BOC is still researching into its effects and is not expected to implement a digital currency anytime soon.[62]

Giving the BOC broader powers

The last proposal for reform involves giving the BOC broader powers over the economy. The central argument behind this proposal is that the BOC is currently unable to effectively control inflation because factors outside their jurisdiction, such as government and regulatory policies, also directly contribute to inflation.[63] Therefore, the BOC must be given wider powers, specifically powers over fiscal and structural policies and financial sector regulation. Without wider powers, any efforts by the BOC to control inflation using only monetary policy are futile, as other policies affecting inflation must necessarily work in tandem.[64] In addition, some proponents of a more powerful BOC also argue that, because of globalization, an international organization of central banks must be created.[65] This is because markets are now more interconnected than ever, and the effect of one countries’ monetary policies will have spillover effects on others. This necessitates a council of representatives of major central banks that regularly report to world leaders on the aggregate consequences of individual central bank policies.

Do we need the BOC?

Monetary policy decisions, like increasing interest rates, are often decisions that are unpopular. Therefore, it is necessary to have a fully independent institution, like the BOC, make such decisions without fear of political pressures or consequences.[66] Monetary policy decision- makers must be able to make decisions for the benefit of the economy only, and not decisions that are popular with the public or benefit a specific government.

As mentioned above, there are no good alternatives to the BOC at this time. Until a good alternative presents itself, Canadians should focus on promoting and maintaining the effectiveness of the BOC. Studies have shown that the effectiveness of monetary policy is directly linked to the level of independence afforded to the central bank making such policies.[67] Therefore, independence is essential to the BOC, and it would not be able to operate effectively under threats of abolishment or other political consequences. Given the recent attacks on the BOC, further action should be taken to confirm and maintain its independence.

Conclusion

While some may feel otherwise, recent data shows that inflation is slowing, and the economy is recovering. Historically speaking and compared to other major economies, the BOC has made better progress towards price and economic stability. While the BOC has been frequently criticized, one must remember that inflation is and will always remain hard to predict. In times of economic instability, the BOC must make policy decisions using lagging data in a global macroeconomic environment that is constantly changing. Given the current economic and regulatory environment, the BOC seems to be on course to control inflation. However, this does not mean that the BOC cannot be improved. In the future, new laws and reforms to the BOC, such as the introduction of a digital currency or broadening of the BOC’s powers, may be implemented to increase its effectiveness.

The author thanks Christy Tang, Articled Student, for her invaluable work on this article.

***

Patrick Cleary is the leader of the Banking + Lending Practice Group, and a member of the Corporate/Commercial Law Group and Executive Team at Alexander Holburn.

Patrick Cleary is the leader of the Banking + Lending Practice Group, and a member of the Corporate/Commercial Law Group and Executive Team at Alexander Holburn.

He has widespread experience in all areas of corporate commercial law with a focus on banking. He acts for financial institutions, representing both borrowers and private lenders in a broad range of secured financing transactions, including syndicated loans, leveraged buyout transactions and asset-based lending and assists them in routine and complex debt financing and secured and unsecured lending transactions.

Find the top-ranked asset-based lending lawyers in Canada here.

In addition, Patrick has been extensively involved in mergers and acquisitions, corporate reorganizations, corporate governance issues, joint ventures and negotiating and drafting commercial agreements. Patrick has acted for real estate development clients in the acquisition, disposition, development, leasing and financing of commercial, industrial and residential developments.

Notably, Patrick has a keen interest in resolving disputes amicably and negotiating mutually satisfying solutions for clients in all corporate/commercial activities. He has acted as counsel in both domestic and international contract negotiations and completed the prestigious Harvard Negotiation Certificate in 2007. Patrick is a member of the Institute of Corporate Directors. He was called to the British Columbia Bar in 2005 and Alberta Bar in 2004.

[1] Mark Rendell, “Bank of Canada delivers half-point rate hike, signals end of aggressive campaign may be near”, The Globe and Mail (9 December 2022), online <www.theglobeandmail.com/business/economy/article-bank-of-canada-interest-rate-hike-announcement-december/>.

[2] Bank of Canada, “Bank of Canada increases policy interest rate by 50 basis points, continues quantitative tightening” (7 December 2022), online: <www.bankofcanada.ca/2022/12/fad-press-release-2022-12-07/> [Bank of Canada 1].

[3] Statistics Canada, “Price Trends: 1914 to today” (last modified 21 December 2022), online: Consumer Price Index Data Visualization Tool <www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/71-607-x/2018016/cpilg-ipcgl-eng.htm> [Statistics Canada 1].

[4] The Conference Board of Canada, “Hope at Last: Canada’s Two-Year Outlook” (30 March 2021), online (pdf): The Conference Board of Canada <www.conferenceboard.ca/e-Library/abstract.aspx?did=11105>.

[5] Timothy Lane, “Our COVID-19 response: Policy actions” (May 2020), online: Bank of Canada <www.bankofcanada.ca/2020/05/ our-policy-actions-in-the-time-of-covid-19/#:~:text=Our%20response&text=We%20have%20responded%20in%20two,key%20 funding%20markets%20functioning%20well.>.

[6] The Conference Board of Canada, supra note 4.

[7] Steven Globerman, “The Outlook for Inflation and Its Links to Monetary Policy” (2021), online: The Fraser Institute <www.fraserinstitute.org/sites/default/files/outlook-for-inflation-and-its-links-to-monetary-policy.pdf>.

[8] Tiff Macklem, “Reflections on 2020” (12 December 2022), online: Bank of Canada <www.bankofcanada.ca/2022/12/reflections-on-2022/>.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Statistics Canada 1, supra note 3.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Bank of Canada, “Bank of Canada maintains policy rate, removes exceptional forward guidance” (26 January 2022), online: Bank of Canada <www.bankofcanada.ca/2022/01/fad-press-release-2022-01-26/> [Bank of Canada 2].

[14] Statistics Canada 1, supra note 3.

[15] Tobias Adrian, Christopher Erceg & Fabio Natalucci, “Soaring Inflation Puts Central Banks on a Difficult Journey” (1 August 2022), online: IMF Blog <www.imf.org/en/Blogs/Articles/2022/08/01/blog-soaring-inflation-puts-central-banks-on-a-difficult-journey-080122>.

[16] Ceyda Oner, “Back to Basics: What Is Inflation?”, Finance & Development (22 March 2010), online: <www.elibrary.imf.org/view/journals/022/0047/001/article-A017-en.xml>.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Adrian, Erceg & Natalucci, supra note 15.

[21] Diane Bellemare, “To curb inflation we must not forget the mistakes of the 1980s and 1990s: Senator Bellemare”, Senate of Canada (12 August 2022), online: <www.sencanada.ca/en/sencaplus/opinion/to-curb-inflation-we-must-not-forget-the-mistakes-of-the-1980s-and-1990s-senator-bellemare/>.

[22] Statistics Canada 1, supra note 3.

[23] Bank of Canada, “Canada’s Economic Future: What Have We Learned from the 1990s?” (22 January 2001), online: Bank of Canada <www.bankofcanada.ca/2001/01/canada-economic-future-what-have-we-learned/>.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Bank of Canada 1, supra note 2.

[26] Statistics Canada 1, supra note 3.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Globerman, supra note 7.

[29] Barry Eichengreen et al, “Rethinking Central Banking” (September 2011), online (pdf): Committee on International Economic Policy and Reform <www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Rethinking-Central-Banking.pdf>.

[30] Bank of Canada 1, supra note 2.

[31] Newfoundland & Labrador Statistics Agency, “Annual Average Unemployment Rate Canada and Provinces 1976-2021” (7 January 2022), online: <www.stats.gov.nl.ca/Statistics/Topics/labour/PDF/UnempRate.pdf>.

[32] Statistics Canada, “Employment and unemployment rate, monthly, unadjusted for seasonality” (2 December 2022), online: Statistics Canada

<www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1410037401&pickMembers%5B0%5D=1.1&pickMembers%5B1%5D=4.1&pickMembers%5B2%5D=5.1&cubeTimeFrame.startMonth=01&cubeTimeFrame.startYear=2022&cubeTimeFrame.endMonth=11&cubeTimeFrame.endYear=2022&referencePeriods=20220101%2C20221101>.

[33] Bellemare, supra note 21.

[34] Ibid.

[35] Nojoud Al Mallees, “Here’s how Canada stacks up against other countries when it comes to high inflation,” National Post (19 November 2022), online: <www.nationalpost.com/pmn/news-pmn/canada-news-pmn/heres-how-canada-stacks-up-against-other-countries-when-it-comes-to-high-inflation>.

[36] Ibid.

[37] Globerman, supra note 7.

[38] Bank of Canada, “Bank of Canada maintains policy rate and forward guidance” (8 December 2021), online: Bank of Canada <www.bankofcanada.ca/2021/12/fad-press-release-2021-12-08/>.

[39] Bank of Canada 2, supra note 13.

[40] Julie Gordan & Steve Scherer, “Hot inflation opens rare attack on Bank of Canada”, CTV News (23 June 2022), online <www.ctvnews.ca/business/hot-inflation-opens-rare-attack-on-bank-of-canada-1.5959770>.

[41] Philip Cross, “Philip Cross: The Bank of Canada has failed, not just Tiff Macklem”, Financial Post (20 May 2022), online <www.financialpost.com/opinion/philip-cross-the-bank-of-canada-has-failed-not-just-tiff-macklem>.

[42] Ibid.

[43] Philipp Carlsson-Szlezak, Paul Swartz, and Martin Reeves, “Weighing the Risks of Inflation, Recession and Stagflation in the U.S. Economy,” Harvard Business Review (10 June 2022), online <https://hbr.org/2022/06/weighing-the-risks-of-inflation-recession-and-stagflation-in-the-u-s-economy>.

[44] Gordon & Scherer, supra note 40.

[45] Ibid.

[46] IMF Executive Board, “Canada: Staff Report for the 2022 Article IV Consultation” (17 November 2022) online: International Monetary Fund <www.elibrary.imf.org/view/journals/002/2022/361/article-A002-en.xml>.

[47] Stephanie Hughes, “Bank of Canada’s Carolyn Rogers flags first-time homebuyers facing ‘trigger rates’ as risk.” Financial Post (22 November 2022), online: <www.financialpost.com/news/economy/bank-of-canadas-carolyn-rogers-flags-first-time-homebuyers-facing-trigger-rates-as-risk>.

[48] Mark Rendell & David Parkinson, “Pierre Poilievre wants to make Canada the world’s ‘crypto capital.’ Why his populist pitch may find fertile ground”, The Globe and Mail (3 April 2022), online: <www.theglobeandmail.com/business/article-pierre-poilievre-wants-to-make-canada-the-worlds-crypto-capital-why/>.

[49] Alex Hern & Dan Milmo, “Crypto crisis: how digital currencies went from boom to collapse”, The Guardian (29 June 2022), online: <www.theguardian.com/technology/2022/jun/29/crypto-crisis-digital-currencies-boom-collapse-bitcoin-terra>.

[50] Ibid.

[51] Ibid.

[52] Marieke Walsh, Mark Rendell & Ian Bailey, “Conservative leadership candidate Pierre Poilievre says he would remove Bank of Canada Governor if he forms government”, The Globe and Mail (12 May 2022), online: <www.theglobeandmail.com/politics/article-poilievre-says-he-would-remove-bank-of-canada-governor-if-he-forms/>.

[53] RSC, 1985, c B-2.

[54] Walsh, Rendell & Bailey, supra note 52.

[55] Ibid.

[56] Ibid.

[57] Gabriel Soderberg et al, “Behind the Scenes of Central Bank Digital Currency: Emerging Trends, Insights, and Policy Lessons” (February 2022), online: IMF Fintech Notes <www.imf.org/en/Publications/fintech-notes/Issues/2022/02/07/Behind-the-Scenes-of-Central-Bank-Digital-Currency-512174>.

[58] Ethan Lou, “Ethan Lou: Why a central bank digital currency could be an inflation-fighter’s best friend,” Financial Post (18 May 2022), online: <www.financialpost.com/fp-finance/cryptocurrency/central-bank-digital-currency-inflation-fighters-best-friend>.

[59] Ibid.

[60] Ibid.

[61] Mark Rendell, “Core inflation puts pressure on Bank of Canada to raise interest rates again”, The Globe and Mail (22 December 2022), online <https://www.theglobeandmail.com/business/economy/article-statscan-november-inflation/>.

[62] Lou, supra note 58.

[63] Eichengreen et al, supra note 29.

[64] Ibid.

[65] Ibid.

[66] Ehsan U. Choudhri & Lawrence L. Schembri., “A Tale of Two Countries and Two Booms, Canada and the United States in the 1920s and the 2000s: The Roles of Monetary and Financial Stability Policies” (14 April 2013), online (pdf): <www.carleton.ca/choudhri/wp-content/uploads/A-Tale-of-Two-Countries-and-Two-Booms-Canada-and-the-United-States-in-the-1920s-and-the-2000s.pdf>.

[67] Ibid.