For mining companies in Canada and across the globe, getting a handle on the “E” of ESG (environmental, social, and governance) issues has long been part of their corporate makeup. However, while that still holds, lawyers who work with mining companies on ESG issues say there is growing emphasis on the “S” and “G.”

“We’re seeing that the focus of mining companies has adapted from simply meeting environmental standards to looking at broader matters of environmental stewardship,” says Robin Longe, a natural resources lawyer in the Vancouver office of Dentons Canada LLP. “At the same time, there’s a lot more discussion going on about what sustainability means, discussion that extends far beyond climate change and the environment.”

Since humans began mine operations, there have been concerns about projects creating environmental issues. Potential water contamination, mine tailings, the overall environmental impact of a project, and what is left when resources deplete are all concerns. However, that is changing as corporate social responsibility evolves to recognize all forms of sustainability and their importance to the company’s and world’s health.

“In the past, the focus has always been on the ‘E’ in ESG in the extractive industries,” says Brad Cahoon, based in Salt Lake City with Dentons. But now, he says, “Sustainability is also being considered from the perspective of social elements, such as labour and governance goals that highlight diversity and inclusion.”

The concepts behind the three letters of ESG are now getting something close to equal billing, Cahoon says, with recent significant concerns for mining companies including limiting water use, purchasing power from renewable energy providers, and partnering with Indigenous peoples. These go far beyond the potential direct damage a mining project can have on the environment.

Shifting goals and challenges

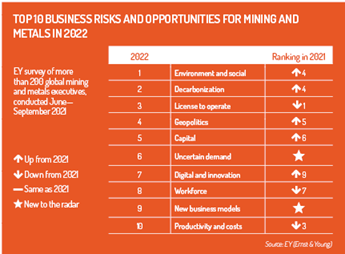

According to an EY (Ernst & Young) survey with C-suite executives in the mining and metals industry, disruption is quickly reshaping the mining and metals sector’s perception of where the most significant challenges – and paths to growth – lie. “The climate crisis and rising stakeholder expectations are increasingly significant forces of change,” the EY survey says. Environment and social concerns took the number one spot in their rankings for the first time, followed by decarbonization and then license to operate, which had held the top position over the past three years.

Two new entrants to the ranking – uncertain demand and new business models – highlight the ongoing volatility in a market still impacted by COVID-19. Still, the survey shows “more opportunities than risks for miners willing to make the transformational changes that can drive long-term value for organizations and the communities they serve.”

Jennifer Wasylyk, a partner and co-chair of the banking and specialty finance and ESG groups at Cassels Brock & Blackwell LLP, says that while ESG issues can apply to any company and its operations, some impact mining companies more than others. “Human rights and security are two big ones,” she says. “What security risks is a project exposed to, and how are those risks being managed? Does a company have appropriate policies, structures, and tools to mitigate human rights risks, which will be even more important in regions with weaker human rights protections?”

Relationships with Indigenous groups and artisanal miners are also integral ESG concerns for mining companies. “That has always been the case,” says Wasylyk, but now there is an emphasis on working with Indigenous groups going far beyond specific laws requiring consultation.

Employee health and safety is another big ESG concern that mining companies must focus on, Wasylyk says. So is management and employee diversity, a hybrid of the social and governance concerns.

ESG also encompasses concepts such as anti-corruption and anti-bribery efforts. “It’s a focus for all companies,” says Wasylyk, “but mining companies, in particular, can operate in jurisdictions where these can be big concerns.”

Wasylyk’s colleague Jen Hansen, a partner in the securities group at Cassels and co-chair of the mining group, notes that the role that ESG plays in the operation of companies, including mining companies, has grown. She says there is also an increasing desire for enhanced disclosure of ESG practices and strategies.

“There is going to be a move away from boilerplate language,” Hansen says. “It won’t be enough for regulators and stakeholders alike.” Stakeholders are more engaged these days on ESG issues and are more prepared to challenge companies, including using their voting rights to ensure issuers live up to the principles they say are important. “We’re going to see an increased call for real action, real expertise, and better disclosure.”

But Wasylyk adds that enhanced ESG disclosure can also create opportunities for companies. “Given the number of investors and lenders that have publicly committed to considering ESG issues when making investment decisions, companies can leverage their ESG policies to attract investment,” says Wasylyk.

Increasing scrutiny and regulation

“What companies are starting to understand is that they will be measured on ESG principles whether they like it or not,” says José Ignacio Morán, a partner of the Dentons’ office in Santiago, Chile. He is the global mining and natural resources practice leader and a member of the firm’s international ESG steering committee.

Morán points out that “companies will likely see more ESG regulation within the next two or three years than we probably have seen in the past 20 years.” And while there are efforts to try to harmonize those regulations worldwide, the reality is that there will likely be differences between countries and regions.

Given this context, Morán says mining companies looking for advice on ESG must first devise a strategy for dealing with the various elements such a plan would encompass. He says questions that need to be asked and answered include: “Is the company and its board covered for loss and liabilities related to ESG? How is the company measuring the impact of their ESG strategy? How are they reporting the strategy and the results of that strategy to stakeholders?”

At Dentons, Morán says the steering committee draws information from experts worldwide to help companies “identify which standards, guidelines, and frameworks they should be adopting.” Firms’ choices will depend on their strategic goals, regulation, and stakeholder expectations.

Ravipal Bains, a Vancouver-based partner with the capital markets and securities practice at McMillan LLP, says many industries, such as mining, are “under a lot of pressure” to demonstrate sustainability. And that comes in several different ways.

“For mining, being sustainable means changes to extraction and processing,” he says. “It relates to efficiencies in reducing emissions from processing and transportation, but also looking across the entire lifecycle, from the early stages to recycling.” While there is progress, Bains says this evolution is also challenging “because you have to develop the technology to allow the industry to become more efficient.”

Morán points out that in Chile, one of the first challenges for mining companies was to reduce continental water consumption and instead turn to seawater. About 25 percent of water consumed in the mining industry is seawater, which is expected to reach 50 percent by the end of this decade. “This is a huge opportunity for us,” he says, adding that there are now developing technologies to incorporate water recirculation into the mining process.

In-house counsel’s key role

For in-house counsel at companies in the mining industry, getting a handle on ESG has taken on more importance, especially as the mining industry has had a checkered past in this area.

Andrew McLaughlin, VP of legal affairs at New Brunswick-based Major Drilling, a leader in specialized drilling and an expert in mineral exploration and mine services, says that over the past several years, he’s seen “undeniable momentum” in the industry on addressing ESG issues.

“ESG has gone from a ‘nice to have’ element of corporate strategy to a ‘must have,’” he says, “as investors, customers, and those in the company’s supply chain demand more from mining companies.”

Says McLaughlin: “This whole idea of ‘greenwashing’ – putting out grand statements on ESG matters and not living up to them – is a thing whose time has come and gone.”

Expanding ESG concepts into areas such as diversity, health and safety, and fair wages has also helped change the environment in companies such as his that are committed to ESG. He says Major Drilling is an industry leader in this area, but that doesn’t mean it is not looking at the environmental side.

McLaughlin says that Major Drilling has recently been looking at ways to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions. However, with operations in 15 companies the task is not easy.

Mining critical minerals

Ironically, while mining is seen as a contributor to ESG problems, especially on environmental issues, recent movement away from fossil fuels also presented some solutions for the mining industry.

For example, Bains points out that the rise of electric car technology and interest in driving electric cars has meant that critical minerals such as lithium and copper – components in making batteries – have become an essential part of sustainability.

“You have to look at these things holistically,” he says. It isn’t easy to build electric cars and reduce emissions in the transportation sector without materials such as lithium, but mining lithium can present ESG challenges. “So, you have to consider the ESG profile of a mining operation – what is being mined, and how it all fits into the entire sustainability picture.”