During the tumultuous time leading up to a bankruptcy or restructuring filing, difficult decisions on the part of the company’s leaders are often necessary. In the midst of an uncertain time, what protections are in place for employees? What issues should leadership consider well in advance of an insolvency situation? Lenczner Slaght’s Christopher Yung answers these questions and more for Lexpert readers.

What is the statutory framework for restructuring and insolvency in Canada?

Canada’s constitution designates bankruptcy and insolvency as a matter of federal jurisdiction, and the two principal federal statutes are the Bankruptcy and Insolvency Act (BIA) and the Companies' Creditors Arrangement Act (CCAA). Though the BIA is typically regarded as a liquidation statute, and the CCAA a restructuring statute, in practice a restructuring can be attempted under either legislation. The CCAA is generally more favoured for restructurings as it is considered to be less rigid in its rules and more flexible in its interpretation. An important distinction is that the CCAA can only be used by corporations, not individuals, and is restricted to larger corporations owing at least $5M to creditors.

As a practical matter, provincial legislation may also become engaged as it is provinces who have the power to legislate in respect of property and civil rights. As an example, a corporation existing under the Business Corporations Act (Ontario)(OBCA), will also be subject to the Employment Standards Act (Ontario). That statute provides that directors of an insolvent employer can be liable for unpaid wages (s. 81). The OBCA itself provides that directors may be liable for up to 6 month’s pay and outstanding vacation pay (s. 131). So while insolvencies are primarily governed by federal statutes, attention also needs to be paid to whether any local legislation is also applicable.

What protections exist for employees of a business attempting a restructuring?

For many businesses, its workforce may be one of its largest obligations, with the payroll being among the biggest determinants of its “burn rate” (i.e., the rate at which it will deplete its available cash reserves). Immediate termination of some of the workforce may be the only option to enable a company to restructure. Employees who are terminated essentially become creditors. Though their termination claims are stayed and cannot proceed during the CCAA’s stay of proceedings, the claims of the employees will be dealt with in any final arrangement, or otherwise. Notably s. 6(5) of the CCAA provides that a court may sanction an arrangement only if it provides for payment to the employees and former employees of an amount at least equal to what they would have received if the company had gone directly into bankruptcy.

But it is equally important that preserving some of the workforce may be essential to preserving value in a future viable business, which is the ultimate goal a restructuring hopes to achieve. In the 2023 CCAA proceedings of Fire & Flower Holdings (a Canadian cannabis store business), the company sought the court’s approval of a “Key Employee Retention Plan” to encourage employees to stay with the company during its restructuring. The plan provided for a two-stage bonus plan, where employees would receive a bonus payment if they remained through to the completion of CCAA proceedings, and an additional bonus payment if the company completed a successful restructuring transaction. In seeking approval for this plan, the company emphasized the instrumentality of retaining key employees to facilitate third party due diligence during the company’s bidding process. In order to secure this bonus payment, a special court-ordered charge was sought over the company’s property, which was ultimately approved by the court.

What about when a business is bankrupt? Where can employees look to collect unpaid wages, severance, etc.? What about benefits in this scenario?

The “scheme of distribution” under s. 136 of the BIA sets out certain priorities for payments to creditors including employees. The fourth item in the scheme is a claim of employees over certain unpaid wages up to a maximum of $2,000. This claim is referred to as “fourth ranking” because it can only be paid if there are sufficient assets available to pay the three claims ranked above it on the list. By the same token the employees’ “fourth ranking claim” must be paid before the payment of any lower ranking claim. Any unpaid wages owing over and above the amount provided for in s. 136 becomes an unsecured claim, which is paid as the last priority, and “pari passu” (in the same proportion) as all other unsecured claims.

These protections under the BIA were not considered adequate, which separately led to the enactment of the Wage Earner Protection Program Act in 2008 (WEPP). Presently, the WEPP provides that employees can receive a maximum of seven weeks' maximum insurable earnings under the Employment Insurance Act, less amounts that are prescribed by WEPP regulations. Payments under the WEPP are paid out of a “Consolidated Revenue Fund” run by the government. In exchange for applying for a WEPP payment, an employee subrogates to the Crown their rights in respect of wages against their employer, and any directors. In essence the claims of various employees become the Crown’s claim, which aims to address the practical challenges that individuals have in incurring legal costs to pursue small claims. Instead the government pays for the claims and consolidates them together into a single larger claim which is more economical to pursue.

Unfortunately a bankruptcy will invariable result in the cessation of employee benefits, and the entitlement to such benefits being categorized as a pre-filing debt. This may result in considerable hardship, particularly when involving disability and long-term health benefits. This is illustrated by the Nortel Networks insolvency, where $100M in disability benefits were owed in relation to former employees, but without adequate trust funds to support the obligation.

One major difference between Canada’s insolvency laws and bankruptcy laws in the United States is our relatively common use of third-party releases. What is the benefit of allowing them, and what are the drawbacks?

It has become more common in Canadian insolvencies for third parties, including directors, officers, DIP lenders, plan sponsors, and financial and legal advisors, to seek a broad release within a CCAA process. The rationale for such releases is that successful restructurings and going concern outcomes will be more likely if parties can actively participate in the CCAA process without constant concern about personal liability. Otherwise it is feared that many parties will be dissuaded from restructuring work, which can often attract litigation from aggrieved stakeholders. A separate reason is that the same parties seeking a release often otherwise would be entitled to assert contribution and indemnity claims against the debtor company, which would lessen the assets available to creditors.

The Canadian experience is somewhat at odds with the US, where third-party releases are not common, and some division exists among federal circuit courts on whether third-party releases are even permitted under Chapter 11 plans. The most recent decision to weigh in on this is the Second Circuit’s May 30, 2023, decision In re: Purdue Pharma L.P., No. 22-110 (2d Cir. 2023), which sided with the availability of such releases under the US bankruptcy code.

While third-party releases are available throughout Canada, it should be noted that they still remain discretionary and fact based. The releases are also subject to two important limitations, the first is that the rationale for the releases will generally not extend to pre-filing claims, and no release may be granted over prohibited matters covered by Section 5.1(2) of the CCAA, including on wrongful and oppressive conduct of directors.

Reverse vesting orders (RVOs) have become more popular, despite not being provided for in either the Companies’ Creditors Arrangement Act (CCAA) or the Bankruptcy and Insolvency Act (BIA). Why have RVOs become prevalent? What risks do they pose to employees?

Traditionally a restructuring would be pursued by way of a plan of arrangement whereby each class of creditors was given an opportunity to vote. In order to obtain the requisite majority approvals, some bargaining would occur which would encourage some value to be shared with various creditors to incentivize them to support a plan. The result would allow a restructured company to emerge with various claims compromised as part of the arrangement, and otherwise extinguished going forward.

The appeal of the RVO is that it can achieve the exact same result (a restructured company unencumbered by old claims), but without the necessity of a creditor vote (and the attendant bargaining process accompanying that vote). In simple terms, in an RVO, the undesirable assets and liabilities are conveyed into a “residual company,” leaving the original corporate entity with only the assets and liabilities it wishes to retain.

Some debate has emerged as to the propriety of this judicial innovation, given that the scheme originally contemplated by the legislature intended for some measure of bargaining to occur to foster value sharing and compromise. But it should be noted that RVOs have emerged to respond to a very practical concern that under the old scheme some creditors could engage in brinksmanship to frustrate a restructuring to extract benefits for themselves. This power would enable some creditors to potentially hold “the sword of Damocles over the head of the significant broad stakeholder group” (Quest University Canada (Re), 2020 BCSC 1883). As such RVOs are likely to remain in the judicial toolbox to ensure value maximizing transactions will occur, though the criterion for their use, and restrictions on their use, may continue to evolve. For now, the courts do not appear ready to recognize RVOs as “the norm" for a restructuring.

For employees as a group the most significant factor is the loss of an opportunity to bargain as part of a plan of arrangement vote. Employee claims all too often fall into the group of unsecured claims, who are “out of the money” because any recoveries in a restructuring will generally go to higher priority secured claims. But because RVOs are approved pursuant to the court’s broad powers under section 11 of the CCAA, it is also the case that they are subject to broad considerations. These include considerations analogous to the well-known Soundair principles, which includes consideration of all parties. Employees will therefore still have an opportunity and forum to express their position, and those pursuing RVOs should still be incentivized to secure employee support.

What else should readers understand about employees whose work is going through bankruptcy?

The period leading up to a bankruptcy or restructuring filing is often tumultuous, with cash and liquidity shortfalls forcing difficult decisions on the part of the company’s leaders. More often than not, these decisions may become the subject of future scrutiny by creditors and other stakeholders if and when a company files under the BIA and the CCAA. Directors and officers who act honestly and in good faith, with a view to the best interests of the corporation, are usually entitled to indemnification under the corporate statute and the company’s by-laws. But where the company itself has insufficient cash on hand to pay for indemnification, that right may prove to be quite valueless. In these situations, directors and officers may face personal liability over claims related to unpaid wages, unpaid tax remittances, environmental liabilities, or breach of trust claims such as under the Construction Lien Act. A company’s leadership should consider these issues well in advance of a potential BIA or CCAA filing, consider what provision should be made to address potential sources of liability, and what coverage is in place including through director and officer insurance.

***

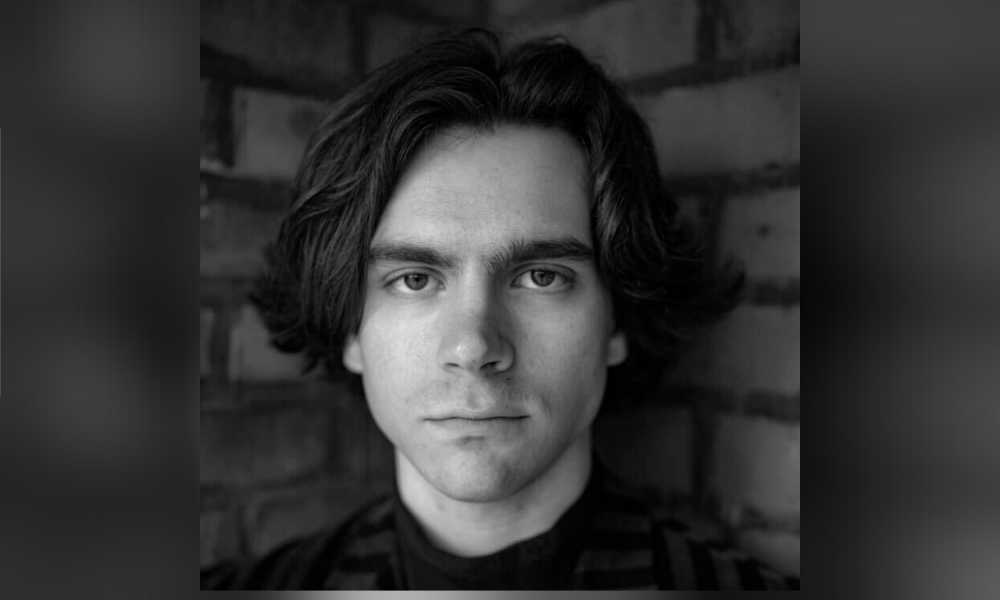

Christopher Yung is a Partner at Lenczner Slaght. Chris has a broad litigation practice, with a focus on commercial litigation, securities litigation, insolvency and restructuring, and shareholder disputes. Prior to joining Lenczner Slaght, Chris practiced with a leading international Canadian firm as a corporate transactional lawyer in Toronto and London, UK, specializing in mergers and acquisitions, corporate finance, and general corporate commercial matters.

Christopher Yung is a Partner at Lenczner Slaght. Chris has a broad litigation practice, with a focus on commercial litigation, securities litigation, insolvency and restructuring, and shareholder disputes. Prior to joining Lenczner Slaght, Chris practiced with a leading international Canadian firm as a corporate transactional lawyer in Toronto and London, UK, specializing in mergers and acquisitions, corporate finance, and general corporate commercial matters.