As the time it takes to settle a dispute through litigation stretches from months into years, alternative dispute resolution has become an increasingly attractive option. However, ADR lawyers say clients must make tough decisions about whether the cost of going this route makes sense, given the complexity of the case and the dollar amount involved.

“There’s a bit of a push and pull among parties in a dispute to consider ADR,’” says Alison Fitzgerald, international arbitration lawyer with Bennett Jones LLP in Ottawa. On the one hand, she says, those who might not have considered alternate dispute resolution in the past realize that it will take years to get to the end of the road if they go through the court system. Arbitration can be much faster.

“On the other hand, going through private arbitration can be an expensive process, so that has to be balanced against what you are looking for in terms of compensation versus the cost of getting to

a resolution.”

Tracey Cohen, co-chair of Fasken Martineau DuMoulin LLP’s commercial litigation group in British Columbia and chair of its national arbitration steering committee, says clients must give “considerable thought” to taking the arbitration path. “It is not always cheaper,” she says.

Cohen adds that parties to a dispute using ADR need to factor in the consequences of the cost award. She says that different legal jurisdictions have different rules on determining costs, “but in arbitration, it tends to be a full recovery of the expenses for a successful party – meaning the loser pays the total amount of the process.”

Still, says Krista Johanson at Borden Ladner Gervais LLP in Vancouver, “the more there are difficulties with the court system when it comes to civil litigation, the more people will use other options.” While the use of ADR in construction industry disputes has been around for a long time, Johanson says, “these days, more sophisticated parties in all sectors are likely to recognize that some disputes are more suitable to be arbitrated than others.”

Johanson also notes that there is often an onus on commercial parties to try to resolve their disputes without access to the courts. “It’s expected that reasonable business people should be able to come up with a solution – but that isn’t always the case. At a certain point, those disputes need to be settled in a binding way.”

Sometimes, “what you need is a decision-maker to resolve things, but it’s becoming increasingly difficult to find that in the court system.”

Hence, ADR has come into its own with a flexible process in which the parties determine what method they want to use, what jurisdiction they wish to handle it in, and who the arbitrators or mediators will be.

“I would say the vast majority of my cases are resolved by mediation,” says Johanson, even if it sometimes is used along with litigation. “It helps everyone to have the incentive of a looming trial date to sharpen their minds, think about their risks, and resolve matters.”

Johanson adds that many of her clients are in the construction sector, where contracts often have detailed clauses addressing how various types of disputes will be resolved, including which would use litigation, which would use mediation or arbitration, whether a mediator or arbitrator is required, or whether the issue would be submitted to an expert.

Johanson’s colleague, Sarah McEachern, adds parties to disputes “are getting more creative” about finding ways to get their arguments heard and will seek ADR even if it is not spelled out as a dispute resolution tool in their contracts.

“I have been contacted by parties who do not have an arbitration clause but can’t get a matter heard quickly asking if I could sit as an arbitrator to hear their case.” She adds that what the parties are looking for is certainty. “Whether through mediation or arbitration, they want clarity at the end of the day and an enforceable award.”

New data backs up arbitration being used more frequently and in more diverse situations. A recent report on international and domestic commercial arbitration by individuals and businesses based in Canada shows that arbitration is increasingly popular and a growing part of Canadian law firms’ businesses.

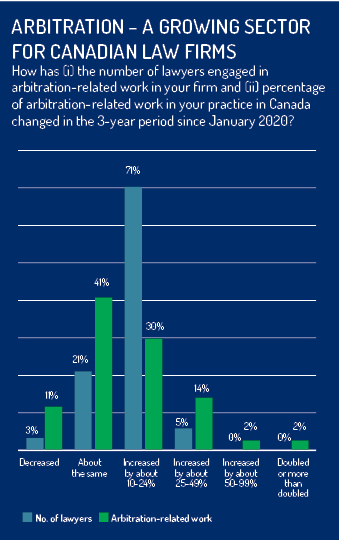

The Canadian Arbitration Report 2024 indicates that of the law firms who responded to the survey – more than 14 firms, including the largest in Canada – 71 percent said the number of lawyers involved in ADR increased between 10 and 25 percent from January 2020 to December 2022, five percent indicated the number of arbitration lawyers increased by 25 to 49 percent, and 21 percent said the number stayed the same.

As for arbitration work law firms did during the same period, 30 percent of those firms who answered said they saw arbitration-related work increase 10 to 24 percent, 14 percent said they had growth between 25 and 49 percent, and 41 percent saw no change.

“The practice of arbitration will see significant growth in the coming years,” co-authors Barry Leon and Janet Walker said in releasing the report this summer. Walker is an independent arbitrator at the Toronto Arbitration Chambers, Atkin Chambers in London, and Sydney Arbitration Chambers. Barry Leon is an arbitrator and mediator with Arbitration Place. FTI Consulting, a global business advisory firm, conducted the survey and data collation and analysis.

When the report was released, Leon noted how more law firms are getting involved in ADR alongside their litigation practices. “Anecdotally, I would say if you walked into a litigation department and asked who there was doing arbitration, a couple of hands would go up. Now it seems that arbitration is a part of everyone’s dispute resolution practice.”

Cohen says that one attraction of arbitration is that “the world is your oyster – the parties can basically agree to anything when it comes to the arbitration process.

“You can have ad hoc arbitration, where the parties create their own process, or you can choose a set of rules from a governing administrating body,” she says. In British Columbia, for example, there’s the Vancouver International Arbitration Centre, which has a set of arbitration rules.

“You can choose the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law process, considered a gold standard, or the Singapore International Arbitration Center.”

Another key advantage to private arbitration or mediation, at least to some, is that it becomes confidential outside the court system. Says Cohen: “If the parties don’t want to air their dirty laundry in public or they are afraid about sensitive data being released, confidentiality can be a significant factor.”

However, lawyers also acknowledge that there is some concern that private and confidential ADR can mean that some important issues could be interpreted and settled without it becoming widely known or making legal precedents.

Fitzgerald of Bennett Jones acknowledges that some confidential matters could help develop the law in areas such as contracts.

“But I wouldn’t say there are so many disputes going into arbitration that you are depriving the public legal system of important discussion and consideration of contractual law principles. Typically, arbitrators would apply the relevant laws in the applicable jurisdiction, and there aren’t such differences between the law and arbitration settlements that make transparency imperative” to push back against a private dispute resolution.

McEachern says another key benefit of using ADR to settle commercial disputes is that parties can choose their arbitrator (or arbitrators in the case of a panel) and pick those they feel understand the industry and nature of the law surrounding the disputed issue.

As for the cost of arbitration, McEachern notes efforts are being made to resolve cases more quickly and for less money. For example, the Vancouver International Arbitration Centre has expedited arbitration for disputes involving lower dollar values. The rules default to a process with no hearing – just written arguments – though one can request a hearing.

“It’s a fairly simple process, and there are some cost savings, which can deal with the criticism that arbitration may be faster than the courts but can be more expensive,” she says. There also is a cap on arbitrator fees depending on the dollar threshold of the case.

Abbey (Junior) Sirivar, partner with McCarthy Tétrault LLP and co-chair of the firm’s international arbitration group, says that the use of ADR “was trending higher” before the COVID-19 pandemic but became even more popular thanks to lockdowns and a lag in filling judicial appointments even as vacancies climbed. The backlog in cases became particularly noticeable in civil disputes, as criminal and family cases took precedence.

With commercial players facing years before a trial and an end to their disputes, Sirivar says, “there has been a near exponential rise in the commercial arbitration space.” He notes that much of this work now involves negotiating arbitration agreements after the disputes arose.

Also, more contracts will have a dispute arbitration clause, to the point where Sirivar says, “I think that in the next five to 10 years, the overwhelming majority of commercial disputes will be resolved through arbitration. This will especially be true among commercial players who have the ability to pay the expenses associated with private ADR.

“Very few commercial or corporate players are in a position to wait [several] years to get their dispute resolved. Most would say that the courts have now become really an ineffective way to resolve disputes, not because of the court’s ability – we actually have excellent judges – but the reality is that there are too many cases and not enough of them.”

Alternative methods, such as arbitration, could well end up being a big part of the answer.