Several trends have reshaped the class action landscape in Canada over the past year. Lexpert talks to top practitioners – Lenczner Slaght partner Brian Kolenda, Rochon Genova LLP partner Golnaz Nayerahmadi, Borden Ladner Gervais LLP partner Stéphane Pitre, and Fasken Martineau DuMoulin LLP partner Peter Pliszka – to identify some of the top developments.

Plaintiffs filing proposed class actions outside Ontario

Several lawyers pointed to one class action litigation trend that has stood out: the noticeable uptick in proposed class actions that could be pursued in Ontario but are being filed in other provinces instead – especially British Columbia.

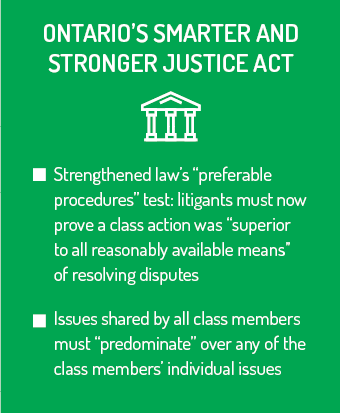

The trend can be traced back to 2020 when Ontario enacted amendments to the province’s Class Proceedings Act. Among the most impactful changes was strengthening the law’s “preferable procedures” test: to have their class actions certified, litigants must prove that a class action was “superior to all reasonably available means” of resolving their disputes.

The amendments also stipulated that issues shared by all class members must “predominate” over any of the class members’ individual issues.

Over the last two years, various courts have issued decisions applying the amendments, Kolenda notes. “The takeaway… from some of those decisions is that Ontario is becoming a less plaintiff-friendly jurisdiction,” he says, adding that there’s a perception that the bar to have proposed class actions certified is higher in Ontario than in other provinces.

Nayerahmadi, who represents plaintiffs, says when the 2020 amendments first went into effect and the courts hadn’t yet interpreted them, “that uncertainty in Ontario surrounding what our legislation now required caused a lot of lawyers to file claims in BC, Quebec, and other provinces.”

The class action bar was particularly concerned that the new superiority and predominance “might stifle class actions, particularly in areas that people generally consider to be very valuable, like systemic negligence claims, institutional negligence claims, claims that have a personal injury element to them that most people consider to be socially important,” Nayerahmadi adds.

But the tide might be turning. In October 2023, the Ontario Superior Court of Justice issued a decision in Banman v. Ontario, which clarified the application of the amendments to a proposed class action alleging systemic negligence and institutional abuse.

The decision confirmed that the new amendments raise the bar to certification but, in practice, “have not substantially varied or changed the class action regime,” Nayerahmadi says.

Banman affirmed that the 2020 amendments haven’t “materially altered the type of cases that we would bring in Ontario,” she adds. While there’s still the potential that the amendments could be brought before the Ontario Court of Appeal or interpreted differently by another court, for the time being, the decision has given plaintiffs the green light to file class actions in Ontario, Nayerahmadi says.

However, Kolenda notes that in early October, the Canadian Bar Association’s class action database indicated that the number of BC filings was still higher than in Ontario.

Whatever Banman “said about the preferable procedure test, there’s still a continuing trend – hard to say whether it’s growing or not – of filings in BC,” he says.

Quebec courts scrutinizing lawyers’ fees

In recent years, Pitre, who is based in Montreal, has observed a growing trend of Quebec courts scrutinizing class action fee agreements arranged by plaintiffs’ lawyers. That trend accelerated over the past year, culminating in decisions where courts have reduced lawyers’ fees or even rejected class action settlements to ensure fairness for class members.

The issue has primarily reared its head in the context of settlements. If class counsel strikes an agreement with plaintiffs that gives them a substantial cut, there’s a growing chance in Quebec that the court overseeing the settlement will contest the fee agreement based on the case resolving too early for class counsel to have earned the full fee, Pitre says. Courts are also cognizant that with class action settlements, class members “are not necessarily getting a lot of money when it’s all said and done,” he adds.

Pitre says Quebec courts are increasingly postponing the approval of lawyers’ fees in cases where funds are distributed to class members who submit individual claims. Historically, class counsel have typically assumed a 100 percent take-up rate by class members to calculate their fee.

“More and more, the courts have said, ‘No, because we get into those situations where when you look at the result, the lawyers are making more money than what is actually given to the members ultimately,’” Pitre says.

“Some judges have said, ‘I’ll approve your settlement, no problem, but I’m not approving, just yet, the fees. We’ll wait to see what the actual take-up rate is, and we’ll give you what is fair.’”

Courts rejecting certification bids and ordering alternative group actions

As both sides of the bar continue to ruminate over whether class actions or other types of actions, like mass torts, are the best way to pursue justice, Nayerahmadi says she’s noticed another growing trend: courts ordering class action cases to be advanced as joinder or group actions instead.

This development has been concerning for plaintiffs’ lawyers because these types of actions are often practically more challenging to manage than class actions, Nayerahmadi says.

“The idea of joinders or group actions is usually proposed by defendants at certification,” Nayerahmadi says. However, “an ongoing concern for plaintiffs is, When that is being directed [by a court] in the absence of the necessary evidentiary foundation to support it, is that kind of case viable? Or is that alternative procedure actually feasible to pursue?”

One high-profile example of this scenario is Carcillo v. Ontario Major Junior Hockey League, a proposed class action brought by hockey players alleging sexual assault and torture. Last year, an Ontario court declined to certify the proposed class, allowing them to appeal the decision or file individual claims instead.

“A question that has arisen through these types of decisions is the extent to which the court can exercise this discretion at certification to determine that an alternative procedure, generally involving either multiple individual actions or group actions, is preferable to the class action that has been advanced on behalf of the plaintiffs,” Nayerahmadi says.

While that question lingers, it’s a trend “that’s probably going to grow and develop further in the coming year or two,” she says.

Opioids litigation

A nationwide wave of lawsuits is proceeding against manufacturers of the highly addictive opioid painkillers on behalf of Canadians who have an addiction, their families, and public health insurers.

According to Fasken’s Pliszka, who is representing defendant Sandoz Canada in these proceedings, there are four class actions in Canada targeting the manufacturers and sellers of opioids. One began in BC and is seeking recovery of the healthcare-related costs incurred due to opioid use on behalf of BC, other provinces, and the federal government.

In late 2023, British Columbia’s application for certification of its proposed class action was heard by a judge of the BC Supreme Court. This is the proposed class action by BC on behalf of itself and all provincial, territorial, and federal governments for recovery of healthcare costs the governments incurred in providing healthcare services to people who developed an addiction to opioids. After a four-week hearing ending just before the seasonal holidays last year, the judge reserved his decision. Pliszka says that regardless of its result, “this decision will be noteworthy because this is the first time that a government in Canada has attempted to initiate a class action on behalf of a class of governments.”

In May, the Supreme Court of Canada also heard the appeal by some of the defendant pharmaceutical companies in that BC class action challenging the constitutionality of the BC statute on which that action is based. The defendants argued that the section in the statute that purports to authorize the BC government to bring a class action on behalf of other provincial, territorial, and federal governments exceeds the limits of the constitutional legislative power of the BC government and infringes the sovereignty of the different governments. The Supreme Court reserved its decision. If the Supreme Court allows the defendants’ appeal and rules that the section in the BC statute is constitutionally invalid, Pliszka says this will preclude certification of the BC class action.

Pliszka says a proposed class action that began to move forward in Alberta is also unusual. This case is a proposed class action by the municipalities of Grande Prairie, Alberta, and Brantford, Ontario, on behalf of all municipalities in Canada seeking, among other things, the recovery of costs they allegedly incurred in providing social and policing services for people who became addicted to opioids. This action was issued several years ago but had remained dormant until this year. The plaintiffs’ lawyers are now taking steps to prosecute that action.

In April, a class action against 16 pharmaceutical companies was authorized in Quebec, and an Ontario opioids class action is proceeding to the second phase of certification based on an amended claim after the court had struck out portions of the original claim.