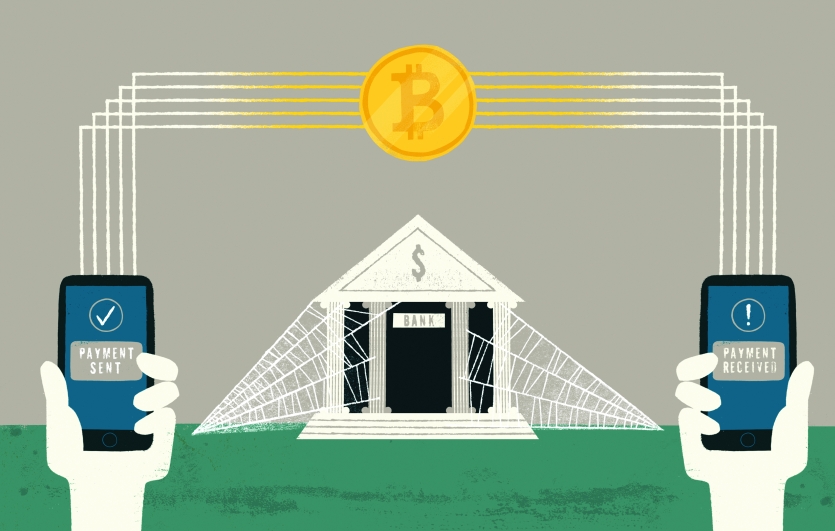

THE MOST IMPORTANT THING IN-HOUSE counsel need to know about fintech — the emerging industry that’s using software to provide financial services — is that the blockchain technology that represents its future focuses on eliminating the middle man. And that goes beyond the banks, credit card companies and clearing houses. Needless to say, lawyers are middle men too.

If there’s any doubt that lawyers are in blockchain’s sights, consider this response from Vitalik Buterin, who co-founded Switzerland-based Ethereum Foundation, a leader in cryptocurrency and blockchain technology, when asked who might suffer from the phenomenon: “I suspect and hope the casualties will be lawyers earning half a million dollars a year more than anyone else,” he said.

While the legal risks have yet to be addressed by regulators, the blockchain revolution is gaining significant traction: former US Treasury Secretary Larry Summers has publicly stated that blockchain is “overwhelmingly likely” to change the financial industry. In fact the technology, which drives Bitcoin cryptocurrency, has already made its mark. “The distributed digital ledger that underlies blockchain technology has certainly been disruptive to the traditional banking structure because it enables transactions that are instantaneous, frictionless and secure,” says Peter Read, President of Peoples Card Services, Canada’s largest issuer of prepaid payment cards.

Proponents of blockchain, meanwhile, say it will make business more efficient by eliminating the traditional stopping points between buyers and sellers, including this era’s corporate behemoths. After all, consider what disruptive forces like Uber, Amazon, iTunes and Ticketmaster have done to the incumbents within their industries. The aforementioned are just a few examples of companies whose prosperity comes from being a more efficient conduit to consumers.

“In-house counsel better understand what the issues are, because many of their companies will have to adapt,” says Theo Ling of Baker & McKenzie LLP in Toronto. “Once they’ve identified the issues, they need to do the proper due diligence and analysis on the steps their clients are taking to confront the blockchain challenge, identify the potential risk and move to mitigate.”

CRYPTOCURRENCIES

When it comes to blockchain technology, fintech is where the stakes are highest. “Financial services are such a cornerstone of the economy,” Ling says. “It’s all about the money.”

But not necessarily money as we know it. Consider the Ethereum Project, which features a decentralized cryptocurrency known as “Ether,” which rivals Bitcoin. It launched in July 2015 and, less than a year later, had a market capitalization in excess of US$1 billion. But Ethereum is not just a cryptocurrency developer: it’s a decentralized application platform that has the potential to extend blockchain beyond peer-to-peer money systems.

Peer-to-peer is the key: blockchain technology and its Ethereum enhancements do not need a centralized server in order to function securely. The technology casts aside centralized financial institutions and replaces them with self-directed computer networks whose core is a transparent but unchangeable distributed ledger open to all members of the network. “In many ways, blockchain is a different version of Napster [the music-sharing technology], in the sense that it’s virtual and peer-to-peer,” Ling says.

Each unit of Ether is unique and identifiable. It cannot be copied and can only be transferred once. Transfers occur when a holder signs a transaction with a private digital key and records it on the shared ledger. The transactions can be seen, but not altered, by anyone on the network. But they occur anonymously, keeping the identities of the payer and payee from prying eyes while at the same time verifying the legitimacy of a transaction through a decentralized consensus mechanism that traces the unchangeable provenance of the currency from the time it was first issued (see In-house Insight on page 63).

“It’s a fundamentally different way of recording and verifying transactions, where multiple computers widely dispersed across the planet execute an algorithm initiated by one of them, but confirmed by them all, through an answer that is held in the blockchain,” says Ross McGowan of Borden Ladner Gervais LLP in Vancouver. “It’s very difficult to interfere, because someone trying to do that would have to get to all of the computers involved.”

Going forward, then, the services of banks and other intermediaries will not necessarily be required to keep track of money and ensure that it has actually been transferred to legitimate parties. In the blockchain, total strangers can keep an accurate ledger of records without resort to trusted third parties or middle men.

GROWING PAINS

To be sure, the technology has its challenges — scalability and security foremost among them.

In June 2016, hackers breached Ethereum’s decentralized autonomous organization (DAO), which acts as a type of investor-directed venture-capital fund. The DAO had been launched only about 45 days before the hack, after being financed by a US$120-million crowdfunding campaign, the largest in history. The fund had 11,000 investors, with the largest holding only a four-per-cent stake.

The hackers gained control of 3.6 million Ethers, worth about US$50 million at the time. Although the funds were put into an account subject to a 28-day holding period under the terms of the governing Ethereum contract, and therefore likely not lost, the breach led to calls that the DAO be shut down.

Despite the problems, blockchain technology continues to represent a significant threat to traditional financial institutions. McKinsey & Co.’s Global Banking Annual Review 2015 predicted that up to 60 per cent of banks’ retail profits could be lost by 2025 to nimble fintech firms. In Canada, similar sentiments prevail.

“We think [the banks] face a material threat to their most profitable business line, Canadian P&C Banking, from innovators who intend to fleece their Golden Geese,” says a report from National Bank Financial Equity Research.

The pickings, it seems, are already there for the taking. “Within five years, Generation Z will make up some 50 per cent of Canadians, and a lot of the millennials who have been watching the economic downturns don’t trust banks,” says Chantel Chapman, National Financial Fitness Coach with Mogo Finance Technology, a Vancouver-based online lender whose stated goal is to create a digital financial brand that emulates what the ride-sharing app Uber has done in the taxi business. “Fintech is a very big subject of discussion today, especially on social media.”

Mogo, which has surpassed one million loans since its founding in 2006 and raised $50 million in a 2015 Toronto Stock Exchange initial public offering, stands for “money on the go.” It’s aimed at young people who want to avoid bank branches. “We can take what is an 11-day loan process at a bank and do it in as little as three minutes,” says Dave Feller, the company’s CEO. “Millennials, who are looking for a different kind of experience, would choose solutions of that kind from a new tech company over solutions that come from a traditional institution.”

A survey by Javelin Strategy & Research found that 40 per cent of Americans with bank accounts visited their branch weekly in 2010, while only nine per cent resorted to mobile transactions. By 2014, the branch visits fell to 28 per cent even as mobile banking tripled to 27 per cent.

Companies like Mogo exploit the user experience. “Fintech seeks to improve the user experience by creating more efficiencies in the market, lower costs per transaction, more transparency for the user, and greater access and a wider range of offerings to the consumer,” Ling says.

Fintech, of course, has been around longer than blockchain, which is merely fintech’s vanguard iteration. But what Ethereum and blockchain’s development have done is force financial institutions to take notice. “A lot of incumbents ignored the rumblings and did not innovate, so the start-ups started to fill the gaps in the market and got some real traction,” Ling says. “Now the financial-services industry is reacting by trying to set up innovation labs.”

Large organizations, however, tend to be slow and inefficient. “They’re not really set up to be innovative, so the innovation labs are actually a second phase,” Ling explains. “The first phase is to co-opt the start-ups.”

It’s already happened: ING Direct Canada, founded in 1997, one of the first online banking services, secured two million customers and US$37.6 billion in assets before Scotiabank bought it for $3.13 billion in 2012.

Partnering is also an option. “We’re working with a Big Five bank that is partnering with tech companies who have developed algorithms for instant credit lending,” says McGowan’s Toronto partner, Stephen Redican. Nowadays, then, companies like Mogo are on the banks’ horizon. “They’ve been talking to us about partnering with them,” Feller says.

So there’s no lack of incentive for startups. “Personal banking has traditionally had a high profit margin of about 40 per cent,” Feller says. “And as Amazon put it, your margin is my opportunity.” So much so that competition from the fintech sector has moved from the lending and investing space to the deposit-taking business.

In January 2016, Vancouver-based financial start-up Koho, in partnership with Visa and Peoples Trust Co., launched its mobile bank to compete with entities like Scotiabank’s Tangerine and CIBC’s PC Financial. It offers direct deposits, bill payments and electronic money transfers for free, as well as budgeting tools aimed at its young target market. A chartered bank holds the funds in partnership with Koho, which makes its money when clients use their Koho Visa prepaid card at establishments that pay a portion of the purchase price to the company.

PLAYERS AND TARGETS

Fintech has been disruptive, there’s no doubt, but it hasn’t achieved revolutionary status quite yet. “Our business isn’t aiming at eating the banks for lunch,” says Mike Martin, CFO at Grow Financial Inc., a Vancouver-based online lender. “Instead, we partner with financial institutions because we can do things more nimbly than they can.” Revolution, it appears, will likely come only if and when the public is prepared to embrace cryptocurrencies and blockchain on a large scale, opening the door for alternative payment systems.

Indeed, according to EY’s FinTech Adoption Index, consumer adoption rates for fintech in Canada have lagged behind five other developed countries, including the US and the UK. Still, Vancouver has become something of a fintech hub in this country. “We’re seeing a lot of start-ups and angel investments in the fintech arena,” says Kareen Zimmer of Fasken Martineau DuMoulin LLP in Vancouver.

That, however, won’t stop financial institutions from behaving as if they are in fact under threat. “Before 2015, few major financial institutions had announced investments in the sector,” write Don and Alex Tapscott, co-authors of Blockchain Revolution: How the Technology Behind Bitcoin Is Changing Money, Business, and the World. “Today Commonwealth Bank of Australia, Bank of Montreal, Société Générale, State Street, CIBC, RBC, TD Bank, Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group, BNY Mellon, Wells Fargo, Mizuho Bank, Nordea, ING, UniCredit, Commerzbank, Macquarie, and dozens of others are investing in [blockchain] technology and wading into the leadership discussion.”

According to the Tapscotts, “financial titans” are also playing venture capitalist in this arena. Among those who have made direct investments in start-ups or incubators are Goldman Sachs, NYSE, Visa, Barclays and UBS. Citigroup, which initially teamed up with Lending Club, an online lender, has now set up its own unit, Citi FinTech. Overall, investment in the sector worldwide rose from $2 million in 2012, to US$2.2 billion in 2014, to almost US$6.8 billion in 2015.

Signs that interest in blockchain technology is ramping up are everywhere. In June 2015, the Canadian Senate’s Committee on Banking, Trade and Commerce released a report that explained why governments should embrace blockchain technology. In the US, the National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws released a draft of the Regulation of Virtual Currency Businesses Act. Even postal services in the US, Australia and Estonia are looking at ways that blockchain technology can improve their financial products like money orders and international money transfers.

In the private sector, meanwhile, The Linux Foundation — a non-profit organization that enables mass innovation through its open-source approach — has recently announced a collaborative effort to advance blockchain technology. And accounting giant Deloitte has already invested in the technology.

It’s a train, in other words, that has already left the station.

THE SMART CONTRACT

From a legal perspective, the “smart contract” aspect of blockchain technology may be of the most direct interest to in-house counsel and other lawyers. Here’s how the Tapscotts define the concept:

“Smart contracts are a form of a program that gives certain conditions and outcomes to money. If there is a transaction between two people, this program can be used to help verify the product or service and whether or not it was fulfilled. Once it has been verified, it can then be transferred to the person’s account.”

According to a report by Mark Walport, the UK government’s Chief Scientific Adviser, the distributed ledger technology underpinning blockchain offers the potential to reduce the cost of paper-intensive processes, including contracts. These contracts, Walport has stated, can provide “cryptographic certainty that the agreement has been honoured in the ledgers, databases or accounts of all parties.”

Ergo, exit the middle man yet again.

No surprise, then, is the Tapscotts’ observation that expertise in smart contracts “could be a big opportunity for law firms that want to lead innovation in contract law.” But the opportunity could be just as fruitful for law departments. Timothy Hill, Technology Policy Adviser at the Law Society of England and Wales told media that Walport’s report makes it clear that blockchains “are a powerful innovation that could have a profound impact on both the law and the provision of legal services.”

The applications seem endless. “[Smart contracts] could be used to declare wills, transfer property or create self-executing contracts,” Hill says. “They also raise profound questions about the future balance between technical code and legal code — something Walport suggests that lawyers and technologists will need to work together to get right.”

Already, a Chicago-based law firm, Empowered Law PLLC, is focusing on digital currencies. The firm provides legal and consulting services to organizations that are using digital currencies, building services with digital currencies or layering technologies on top of blockchain-based systems. The firm also acts as consultants to lawyers seeking to bridge the gap between practice and technology.

Of particular interest is Empowered Law’s list of primary practice areas, which includes asset protection and estate planning, decentralized and distributed network governance, escrow services, expert witness services, mediation services, risk assessment and management, and technology-based governance solutions.

In the UK, meanwhile, Magic Circle firm Allen & Overy is partnering with Deloitte to create a service called MarginMatrix that codifies banking law in various jurisdictions and automates document drafting to address statutory requirements. A&O claims that the system will cut drafting time from three hours to three minutes, and will reduce the time required to handle 10,000 contracts from 15 years to 12 weeks. MarginMatrix could also remove the need to have separate legal providers in various jurisdictions.

Find out the 3 major banking laws in Canada in this article.

KNOWN UNKNOWNS

For all its promise, blockchain technology also poses serious legal risks that, as of yet, have not been adequately addressed.

A survey earlier this year by Baker & McKenzie and the Euromoney Institutional Investor Thought Leadership canvassed 424 executives and experts from financial institutions, fintech companies and the artificial intelligence field. According to their report, entitled Ghosts in the Machine, 56 per cent of all survey respondents who had some legal background, and 44 per cent of respondents overall, did not completely understand the risks that have been associated with artifical intelligence.

“This is a remarkable finding as it appears to clash with financial institutions’ (“FIs”) approach to legal risk,” says B&M in a commentary. “FIs have low appetite for conducting any business or activity with high legal risk, and both numbers — 44% and 56% — are off the radar from the perspective of acceptable risk levels.”

B&M suggests financial institutions involve their law departments in the development of AI so as to help gauge the legal risks. “In the past, legal teams were often involved too late in the process and the opportunity to input during the design phase was missed,” B&M states. “This can lead to wasted time, effort and cost as well as inhibit the speed to market.”

But there’s considerable uncertainty involved for those giving advice in this arena. “How do you work within the legislative framework when the legislation is not keeping up?” asks Lisa Skakun, Chief Legal & Administrative Officer at Mogo.

Paying attention, it seems, might be a good way for law departments and their external lawyers to start.

Julius Melnitzer is a freelance legal-affairs writer in Toronto.