ANY BUSINESS PERSON who walks into a law firm to discuss a proposed merger or an acquisition may be startled to see a privacy lawyer at the table alongside the corporate team.

Indeed, a few years ago a privacy lawyer wouldn’t have been present, says Lyndsay Wasser, co-chair of McMillan LLP's privacy and data protection and cybersecurity groups. “Three years ago I don’t think most lawyers or most businesspeople even had this on their radar.”

But now they must, and they do. Wasser delivered a one-hour presentation to her firm’s M&A group last year on why she or someone else from her group should be brought in when a client is considering a deal. It worked, she says. “They’re reaching out to me very regularly now.” That’s because they, like lawyers at almost every other business law firm, have started to appreciate that privacy considerations can impact a deal’s desirability. A firm that is not in compliance with privacy laws may have a lower valuation than one that isn’t, deal lawyers say.

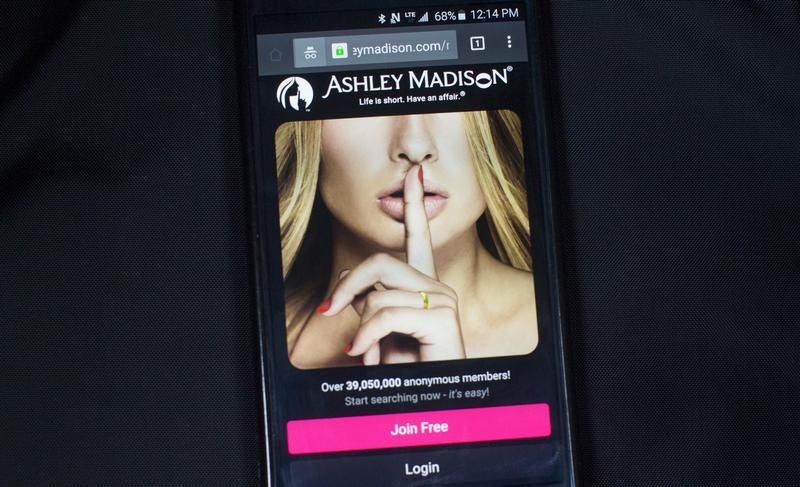

A potential buyer has the right to ask any question and look at any material that will help it accurately value the business and decide whether to greenlight a deal; but today, that must be balanced against privacy compliance. When the transaction involves a business-to-consumer company –– an online retailer, a dating site, a messaging app, or any company that collects its customers’ information –– the buyer must start by ensuring the target company has been onside with applicable privacy laws.

“You do that by asking for disclosure of things like their privacy policies and any documents related to their internal privacy-compliance program,” says Wasser. “You also want to have disclosure of any allegations of improper handling of personal information, or complaints, and anything to do with outsourcing of information. You want to look at outsourcing and contracts with service providers with whom the company shares personal information to make sure they have all the appropriate privacy provisions.”

Assuming the deal goes ahead, she says, the buyer should be asking for a representation and warranty that the organization is in compliance with privacy laws as well as with its own privacy policies, which should have been disclosed in due diligence, and any privacy and data-protection provisions in contracts with other parties.

That’s key, because the buyer’s obligation to respect the customers’ privacy doesn’t end after the deal closes, says Wasser, a Certified Information Privacy Professional in Canada.

“The privacy legislation has specific provisions in it that say you can only transfer information without consent of the individual –– and we’re talking about personal information –– to the extent it’s going to be used for the same purposes it was used for before the transaction happened. The purchaser can’t now use that information for a completely unrelated purpose that the individuals never agreed to without going back and getting their consent.”

Protecting information

Potential buyers aren’t the only ones running up against Canada’s privacy laws, which are among the strictest in the world. A seller will be expected to give bidders or potential buyers access to information about the target's customers, employees and contractors. Yet for large companies with thousands of employees, customers and contacts –– and for public companies with market-disclosure restrictions –– seeking individual consent to share that information for a potential transaction that has not been publicly announced is a non-starter.

So how do they hand over that information while protecting themselves? In sharing information for the purposes of conducting a transaction, sellers can generally rely on the deal-friendly “business transaction exemption,” says Molly Reynolds, a privacy litigator at Torys LLP in Toronto.

The Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act, Canada's federal private-sector privacy law, contains a provision that permits sellers to share private information without advanced consent if it’s for a proposed acquisition. It requires the seller to put some contractual safeguards in place during the evaluation process and, if the sale goes ahead, the buyer has to notify individuals after the fact that their information was transferred.

Reynolds says these safeguards, which kick in before potential buyers can access a data room, require those potential buyers to sign agreements to the effect that they won’t use or disclose the information for any purpose other than evaluating the deal, that they’ll put the same protections in place that the seller is already using to minimize chances the personal information will leaked or hacked, and that they’ll destroy any of the personal information that was shared without retaining any copies if the deal doesn’t go through.

But there’s a catch, Reynolds warns. The exemption has a built-in necessity test: unless the personal information is absolutely necessary to the buyer or bidder evaluating the deal, it can’t be shared. “You have to be able to prove, if you’re ever challenged by a regulator, that sharing the information actually was necessary.”

While information about employee salaries might be necessary in evaluating the liabilities and cost of operating the business, she says, employees’ social insurance numbers “are very unlikely to be needed, so there’s some internal vetting that has to be done before information is uploaded. That can actually be quite time-consuming.”

Québec landscape

Lawyers working on mergers and acquisitions in Québec don’t have the benefit of the business transaction exemption, and it is the only such province not to, says Marie-Hélène Constantin, a partner at Blake Cassels & Graydon LLP in Montreal. “So that’s an obstacle that has to be overcome.”

While sellers will get the same types of agreements that Reynolds described before they allow a prospective buyer access to certain data, that is not necessarily enough protection because, without the exemption, private information cannot be shared in any context.

“There’s no easy way to do this,” says Constantin, adding that the workaround varies from deal to deal. But generally speaking, lawyers will look at whether personal information is required and, if it is, “whether it can be aggregated or anonymized.” She says she and her colleagues will also examine whether the initial consent agreement stipulates that the information can be shared as part of any sale of the business, which is becoming more common. If not, they may have to explore whether individual consent for disclosure of personal information can be obtained.

Yes, it causes extra work and makes transactions more expensive. But with headline-grabbing data breaches — from Ashley Madison to Equifax — serving to heighten awareness of the importance of protecting personal information, it doesn’t seem likely that privacy lawyers will be kicked off deal teams anytime soon.

If you need help relating to the collection, use, disclosure and maintenance of personal information, consult the best data privacy lawyer in Canada here.