EVEN AS CANADA HUSTLES to play catch-up on the international trade scene through its ongoing pursuit of bilateral investment treaties (BITs) with developed and emerging nations, it faces its first non-NAFTA investment claim and the first BIT claim against it by a developing-country investor — and from no less a trading power than Egypt.

The claim comes in the form of a request for arbitration by Global Telecom Holding (GTH), registered in June with the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) under the Canada-Egypt BIT of 1996. The parties have not yet provided details, but the dispute almost certainly arises from the failed attempt by GTH (operating as Orascom Telephone) to buy a controlling interest in Wind Mobile Canada, a wireless service provider, about three years ago. GTH maintains that it was treated unfairly by the Canadian government, forcing it to withdraw its bid.

The irony here is palpable. After all, investor-state dispute-resolution mechanisms were originally intended to protect investors from developed countries against unfair treatment from developing countries, where democracy and the rule of law were not necessarily priorities. As far back as 1994, NAFTA’s Chapter 11 was included in the treaty to protect US and Canadian investors against corruption in Mexico. “Investor-state disputes were intended to depoliticize the process,” says Tina Cicchetti of Fasken Martineau DuMoulin LLP in Vancouver. “It used to be that the best available option for investors was try to convince their governments to either negotiate for them or pull up the gunboats to resolve what was essentially a commercial dispute.”

GTH’s claim flips the script. It is the first BIT dispute in which Canada finds itself on the defensive, though its subject matter is probably no surprise to seasoned observers. The case is squarely within the realm of the cultural protectionism allegations that have long sullied Canada’s reputation as a free-trade advocate. “My impression is that Canada cycles between encouraging foreign investment and its nationalist concerns,” says Catherine Gibson of Covington & Burling LLP in Washington, DC.

There’s really no dispute that Canadian governments have long granted special status to the country’s “cultural industries.” The policy has for many years been an irritant to trading partners, the subject of extensive discussions in trade negotiations, and the catalyst for international arbitration claims against Canada under the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and at the World Trade Organization (WTO).

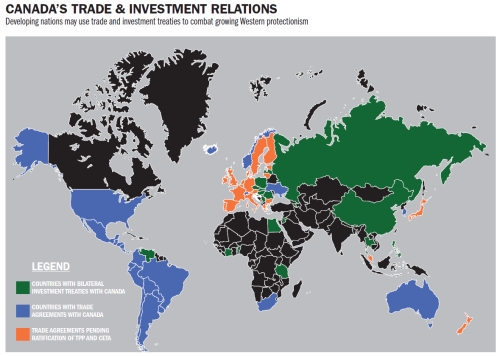

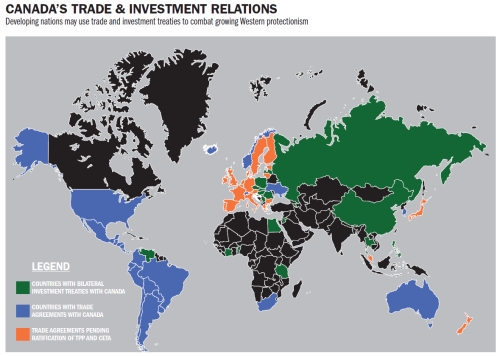

For the most part, these claims have come from other industrialized countries like the US, the EU and Japan. But, just as this country begins to wade into multinational free trade agreements like the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) and the Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement (TPPA), the worm may be turning in favour of developing nations.

“Canada faces, for the first time, a claim under treaties that were often concluded at a time when capital flows were not so much of a two-way street,” writes Luke Petersen, editor and publisher of Investment Arbitration Reporter. “These changes in the direction of investment flows, as well as Canada’s pursuit of treaties with major capital exporters like China, India, and the European Union, could presage more such claims in future.”

TO DATE, CANADA has been involved in BIT arbitrations only as the nationality of a complaining company. Many of the aggrieved investors have been mining companies who have been victims of the phenomenon known as “resource nationalism.”

TO DATE, CANADA has been involved in BIT arbitrations only as the nationality of a complaining company. Many of the aggrieved investors have been mining companies who have been victims of the phenomenon known as “resource nationalism.”

In the typical resource nationalism scenario, underdeveloped countries go out of their way to attract foreign investment with incentives and favourable contracts or licences, and companies then invest heavily in the infrastructure necessary to extract the riches. Once the major investments are in place, the governments of these developing states try to renegotiate, and if they can’t, resort to threats, taxes, regulatory hurdles or direct or indirect expropriation to get what they want.

Clearly, that’s not the Canadian way. But when it comes to cultural protectionism, a long history of formal and informal international claims against Canada have combined with a lack of transparency to give the country something of a black eye.

Consider the facts behind GTH’s withdrawal in 2013 of its attempt to take control of Wind. The company had provided much of the financial backing when Wind entered the Canadian wireless market in 2008, but foreign-ownership rules limited its stake to a 32-per-cent voting interest and a 65.1-per-cent equity interest.

In 2012, the Canadian government relaxed foreign ownership limits on small telecoms. GTH sought to buy out Wind owner Anthony Lacavera. Despite the relaxation of the foreign-ownership rules, the Investment Canada Act (ICA) mandated a review of the transaction. Media reports suggested that a seemingly straightforward review had been subject to longer-than-usual delays, but before the review could be completed, GTH withdrew its application. The company stated that its decision came following discussions with the government as part of the review process.

Observers speculated that the government was concerned that GTH intended to sell the company after acquiring control, but no one outside the stakeholders circle really knows what prompted the government to drag out the affair and cause GTH to drop its bid. According to Milos Barutciski of Bennett Jones LLP in Toronto, the lack of transparency in ICA reviews contributes significantly to protectionist allegations against Canada. “Any protectionist reputation we have is due to a handful of sectors and a few ICA cases,” he says.

Despite the government’s protestations as to the objectivity of the ICA review process, Barutciski maintains that ICA reviews produce “totally political” results. “The first thing foreign investors involved in any significant transaction hear is that they’re going to be subject to a political review, and they don’t like going through what they regard as nonsense,” he says. “The government also has a habit of trying to squeeze something, whether it relates to jobs, or language rights, or R&D commitments, from the foreign investor just before closing. So we end up shooting ourselves in the foot by leaving a sour taste that has the flavour of a banana republic in the mouths of foreign investors.”

If history is any indication, that “bad taste” has been lingering for a while. Just a few years after NAFTA came into force, the CRTC stopped the US channel Country Music Television from continuing its Canadian operation after granting a license for a new country music channel to a Canadian entity. Subsequently, the US government conducted an investigation that determined that Canada acted in an unreasonable and discriminatory way.

The parties ultimately resolved the issues privately, but its aftermath is still felt. “The US government remains concerned about the discriminatory broadcasting policies that exist in Canada,” Gibson says. Indeed, pressure from the US could well have factored into the CRTC’s decision earlier this year to put an end to Super Bowl “simulcasting.” The new policy finally allowed Canadian viewers watching the Super Bowl on US channels to see the highly vaunted half-time commercials that had been denied them for years — all in the name of protecting advertising revenue for Canadian broadcasters.

Canada’s cultural protectionism hasn’t fared well at the WTO either. In the late ’90s, the US filed a WTO claim alleging that Canada had violated the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade by giving preferential tax treatment to Canadian magazines. The WTO ruled in favour of the US, noting that Canada had “admitted that the objective and structure of the tax [was] to insulate Canadian magazines from competition in the advertising sector, thus leaving significant Canadian advertising revenues for the production of editorial material created for the Canadian market.”

More recently, Canada took another hit from the WTO, albeit not in the cultural industry sector. The dispute found its origins in Ontario’s FIT Program, which allowed renewable energy producers to lock into fixed-price electricity contracts at premium rates. Eligibility for the program, however, depended on the use of locally produced materials. Japan and the EU complained. In 2013, the WTO Appellate body found that FIT violated Canada’s WTO obligations by treating imported goods less favourably than domestic goods.

Canada is also the most sued country under NAFTA. Investors have brought some 35 claims against Canada compared to the 20 brought against the United States. Even Mexico, the original target of NAFTA’s investment-protection provisions, has faced only 22 cases. Canada has lost or settled six claims and paid out some $170 million in damages; Mexico has lost five at a cost of $204 million; the US has never lost.

According to some observers, Canada’s history, seen in the current economic climate, portends even more protectionist measures here. “The environment is very different from 25 years ago when free trade was all the rage,” says Brenda Swick of Dickinson Wright LLP in Toronto. “There are strong populist trends to protecting local production, workers and the environment, and it would be naïve to think that we’re not going to see more government action in support.”

Swick points to Alberta’s recent subsidy for its own beer producers, which she says could “well be offside” international trade and investment agreements. Others question whether BC’s recent surtax on foreign buyers of residential properties will survive international scrutiny. “I think it’s very conceivable that we could start seeing challenges under many BITs as Canada embarks on a path of introducing protectionist measures under the Liberal administration,” Swick says.

It’s not that Canadian legislators are blind to cultural protectionism. Various exemptions for these industries are expressly provided for in Canada’s BITS and NAFTA. They cover not only print publications but their distribution; the production, distribution, sale or exhibition of film or audio, video and audio music reporting; radio communications intended for reception by the public; all radio, television or cable broadcasting undertakings; and all satellite programming and broadcast network services.

The exemptions cut a wide swath. United Parcel Service of America (UPS) discovered just how wide when the company filed a US$160-million NAFTA claim in 2000. UPS alleged that Canada had provided improper subsidies to Canadian publications that gave Canada Post an advantage over private courier services. Seven years later, the tribunal ruled against the UPS, holding that the cultural industries exemption, which it called “admittedly broad” and “expansive,” applied.

The difficulty with the exemptions is that they differ, and to varying degrees. NAFTA, for example, allows the United States to retaliate if Canada invokes the exemptions. Many BITs, like the one with Egypt that governs the GTH dispute, were negotiated in a world that perceived money moving just one way: from developed to developing countries. The upshot is that many were not drafted with protections for the developed country in mind.

That, obviously, has changed. “In the past, Canada may not have thought about cross-investment when it was negotiating trade treaties, but global money has no need for a home anymore,” says Barry Appleton of Appleton & Associates in Toronto. Unlike some European countries, Canada has not taken any step to update its BITs.

Going forward, both CETA and the TPPA maintain the cultural exemption for Canada. “These new agreements are not aspirational but recognize what’s actually going on in the world by allowing more protectionism for everyone,” Appleton says. “In doing so, they give government more latitude to discriminate against foreigners in their public policy.”

The lawyer, however, also maintains that both CETA and the TPPA were conceived and drafted too hastily, without sufficient consultation. “The treaties have lots of holes and problems generally, and eventually these errors will manifest themselves into disputes.”

WHAT WILL CHANGE DRAMATICALLY, at least under CETA, is the way in which disputes will be resolved — and the issue could not be more controversial.

When the European Commission invited comment on investor-state arbitration in 2014, the 145,000 responses crashed its computers. The respondents were overwhelmingly against the current system, essentially a private one, where arbitrators appointed and paid for by the parties are the adjudicators. But it’s not just Europe. Many countries, including Canada and the US, are seeing a backlash against investor-state arbitration in its current form, where the mechanism is often viewed as an infringement on sovereignty. Other criticisms of the current system are the lack of judicial independence and the lack of standing for third parties who may have an interest in the proceedings.

The upshot is that the final text of the Comprehensive and Economic Trade Agreement, signed in February 2016, does away with arbitrators appointed by the parties and replaces them with a permanent tribunal roster established by governments with no input from investors. The 15-person roster will be composed of five Canadian members, five from the EU and five from other countries. Arbitrators will be selected randomly from that group. “The roster will enable Canada and the EU to control which experts sit on arbitrations to ensure that they are sensitive to government perspectives,” writes Greg Tereposky in a Borden Ladner Gervais LLP bulletin.

CETA also establishes an appellate tribunal to review awards. Its jurisdiction will be limited to errors of law and manifest errors in fact. “This will without doubt improve the consistency and predictability of the interpretation and application of investment protection provisions,” Tereposky states.

Cicchetti, for her part, is skeptical that a permanent court is the right way to go. “The parties won’t have an opportunity to choose the decision-maker, and who knows just how these people will be chosen?”

But professor Gus Van Harten of Osgoode Hall Law School at York University says that the CETA arrangement is a definite improvement and augurs well for Canada. “Canada has been gung-ho on accepting the old system even when it’s the country in the more vulnerable position, as it did when it signed on to NAFTA. Since then, we have led the pack among Western nations in ceding sovereignty.”

Cases like GTH, Van Harten adds, are now exposing risks that Canada did not expect when it signed the BIT with Egypt. “Even if the risk of losing is small, there’s a potential for a $1-billion award for lost profits,” he says. “Surely that’s enough to impact decision-making in this country.”

WHAT, THEN, LIES AHEAD for investor-state arbitration? Is Canada going to see a decided uptick or not?

Generally speaking, as BITs have proliferated globally — there are now just under 3,000 in force — so have the number of investor-state disputes. ICSID, which hears an estimated two-thirds of BIT disputes, administered 38 in 2011. That number, itself a record, gave way to a new high of 52 cases in 2015. Growth has been particularly noticeable during this century: just 69 cases were registered between 1972 and 1999, while some 500 were registered between 2000 and 2015.

Sheer numbers suggest that CETA could in itself contribute to an upsurge in arbitrations involving Canada. When and if the treaty is ratified by all parties, Canada will effectively have a BIT with every one of the EU nations, including the original EU members, with whom it currently has no investment-protection treaties.

The reforms envisaged by CETA to the arbitration system could contribute as well. “I think if the reforms that are proposed are actually put into place, they could have a significant impact on arbitration claims,” Van Harten says.

Bartuciski also believes that the trend will continue, but that CETA and TPP will in themselves not be significantly influential in increasing the number of disputes. “The changes that these treaties make to the investor-protection regime are quite modest, and what we’re basically looking at is a NAFTA-type regime with the wrinkle of a permanent court.”

Gibson’s view is that a huge wave of investor-state claims is not in the offing. “They’re expensive, they bring a lot of publicity, and investors know that states win most of the claims, so there are only a certain number of claimants who will resort to arbitration.”

But there may be a wild card in the mix: third-party litigation funding has made its way to investor-state disputes. Companies like the $300-million Burford Group, the world’s largest private litigation funder, and Calunius Capital, both based in the United Kingdom, are now providing financing. “Investor-state disputes are attractive to third-party funders because they always involve big dollars,” says Robert Wisner of McMillan LLP in Toronto, who represents a number of junior mining companies who have obtained such funding for ICSID cases.

Third-party funders don’t care much whether the complainant is based in developing country or a developed one: all they really care about is whether the case has merit and whether they can recover any award. Indeed, financing a claimant from a developing country may be more attractive to third-party funders because the prospects of actual recovery from developed countries is a much safer bet than trying to collect from poor countries. The upshot is that third-party funding could be a game-changer in the investor-state dispute arena.

So what’s next? If it works for Egypt, why wouldn’t it work for Burundi?

Julius Melnitzer is a freelance legal-affairs writer in Toronto.

The claim comes in the form of a request for arbitration by Global Telecom Holding (GTH), registered in June with the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) under the Canada-Egypt BIT of 1996. The parties have not yet provided details, but the dispute almost certainly arises from the failed attempt by GTH (operating as Orascom Telephone) to buy a controlling interest in Wind Mobile Canada, a wireless service provider, about three years ago. GTH maintains that it was treated unfairly by the Canadian government, forcing it to withdraw its bid.

The irony here is palpable. After all, investor-state dispute-resolution mechanisms were originally intended to protect investors from developed countries against unfair treatment from developing countries, where democracy and the rule of law were not necessarily priorities. As far back as 1994, NAFTA’s Chapter 11 was included in the treaty to protect US and Canadian investors against corruption in Mexico. “Investor-state disputes were intended to depoliticize the process,” says Tina Cicchetti of Fasken Martineau DuMoulin LLP in Vancouver. “It used to be that the best available option for investors was try to convince their governments to either negotiate for them or pull up the gunboats to resolve what was essentially a commercial dispute.”

GTH’s claim flips the script. It is the first BIT dispute in which Canada finds itself on the defensive, though its subject matter is probably no surprise to seasoned observers. The case is squarely within the realm of the cultural protectionism allegations that have long sullied Canada’s reputation as a free-trade advocate. “My impression is that Canada cycles between encouraging foreign investment and its nationalist concerns,” says Catherine Gibson of Covington & Burling LLP in Washington, DC.

There’s really no dispute that Canadian governments have long granted special status to the country’s “cultural industries.” The policy has for many years been an irritant to trading partners, the subject of extensive discussions in trade negotiations, and the catalyst for international arbitration claims against Canada under the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and at the World Trade Organization (WTO).

For the most part, these claims have come from other industrialized countries like the US, the EU and Japan. But, just as this country begins to wade into multinational free trade agreements like the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) and the Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement (TPPA), the worm may be turning in favour of developing nations.

“Canada faces, for the first time, a claim under treaties that were often concluded at a time when capital flows were not so much of a two-way street,” writes Luke Petersen, editor and publisher of Investment Arbitration Reporter. “These changes in the direction of investment flows, as well as Canada’s pursuit of treaties with major capital exporters like China, India, and the European Union, could presage more such claims in future.”

TO DATE, CANADA has been involved in BIT arbitrations only as the nationality of a complaining company. Many of the aggrieved investors have been mining companies who have been victims of the phenomenon known as “resource nationalism.”

TO DATE, CANADA has been involved in BIT arbitrations only as the nationality of a complaining company. Many of the aggrieved investors have been mining companies who have been victims of the phenomenon known as “resource nationalism.”In the typical resource nationalism scenario, underdeveloped countries go out of their way to attract foreign investment with incentives and favourable contracts or licences, and companies then invest heavily in the infrastructure necessary to extract the riches. Once the major investments are in place, the governments of these developing states try to renegotiate, and if they can’t, resort to threats, taxes, regulatory hurdles or direct or indirect expropriation to get what they want.

Clearly, that’s not the Canadian way. But when it comes to cultural protectionism, a long history of formal and informal international claims against Canada have combined with a lack of transparency to give the country something of a black eye.

Consider the facts behind GTH’s withdrawal in 2013 of its attempt to take control of Wind. The company had provided much of the financial backing when Wind entered the Canadian wireless market in 2008, but foreign-ownership rules limited its stake to a 32-per-cent voting interest and a 65.1-per-cent equity interest.

In 2012, the Canadian government relaxed foreign ownership limits on small telecoms. GTH sought to buy out Wind owner Anthony Lacavera. Despite the relaxation of the foreign-ownership rules, the Investment Canada Act (ICA) mandated a review of the transaction. Media reports suggested that a seemingly straightforward review had been subject to longer-than-usual delays, but before the review could be completed, GTH withdrew its application. The company stated that its decision came following discussions with the government as part of the review process.

Observers speculated that the government was concerned that GTH intended to sell the company after acquiring control, but no one outside the stakeholders circle really knows what prompted the government to drag out the affair and cause GTH to drop its bid. According to Milos Barutciski of Bennett Jones LLP in Toronto, the lack of transparency in ICA reviews contributes significantly to protectionist allegations against Canada. “Any protectionist reputation we have is due to a handful of sectors and a few ICA cases,” he says.

Despite the government’s protestations as to the objectivity of the ICA review process, Barutciski maintains that ICA reviews produce “totally political” results. “The first thing foreign investors involved in any significant transaction hear is that they’re going to be subject to a political review, and they don’t like going through what they regard as nonsense,” he says. “The government also has a habit of trying to squeeze something, whether it relates to jobs, or language rights, or R&D commitments, from the foreign investor just before closing. So we end up shooting ourselves in the foot by leaving a sour taste that has the flavour of a banana republic in the mouths of foreign investors.”

If history is any indication, that “bad taste” has been lingering for a while. Just a few years after NAFTA came into force, the CRTC stopped the US channel Country Music Television from continuing its Canadian operation after granting a license for a new country music channel to a Canadian entity. Subsequently, the US government conducted an investigation that determined that Canada acted in an unreasonable and discriminatory way.

The parties ultimately resolved the issues privately, but its aftermath is still felt. “The US government remains concerned about the discriminatory broadcasting policies that exist in Canada,” Gibson says. Indeed, pressure from the US could well have factored into the CRTC’s decision earlier this year to put an end to Super Bowl “simulcasting.” The new policy finally allowed Canadian viewers watching the Super Bowl on US channels to see the highly vaunted half-time commercials that had been denied them for years — all in the name of protecting advertising revenue for Canadian broadcasters.

Canada’s cultural protectionism hasn’t fared well at the WTO either. In the late ’90s, the US filed a WTO claim alleging that Canada had violated the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade by giving preferential tax treatment to Canadian magazines. The WTO ruled in favour of the US, noting that Canada had “admitted that the objective and structure of the tax [was] to insulate Canadian magazines from competition in the advertising sector, thus leaving significant Canadian advertising revenues for the production of editorial material created for the Canadian market.”

More recently, Canada took another hit from the WTO, albeit not in the cultural industry sector. The dispute found its origins in Ontario’s FIT Program, which allowed renewable energy producers to lock into fixed-price electricity contracts at premium rates. Eligibility for the program, however, depended on the use of locally produced materials. Japan and the EU complained. In 2013, the WTO Appellate body found that FIT violated Canada’s WTO obligations by treating imported goods less favourably than domestic goods.

Canada is also the most sued country under NAFTA. Investors have brought some 35 claims against Canada compared to the 20 brought against the United States. Even Mexico, the original target of NAFTA’s investment-protection provisions, has faced only 22 cases. Canada has lost or settled six claims and paid out some $170 million in damages; Mexico has lost five at a cost of $204 million; the US has never lost.

According to some observers, Canada’s history, seen in the current economic climate, portends even more protectionist measures here. “The environment is very different from 25 years ago when free trade was all the rage,” says Brenda Swick of Dickinson Wright LLP in Toronto. “There are strong populist trends to protecting local production, workers and the environment, and it would be naïve to think that we’re not going to see more government action in support.”

Swick points to Alberta’s recent subsidy for its own beer producers, which she says could “well be offside” international trade and investment agreements. Others question whether BC’s recent surtax on foreign buyers of residential properties will survive international scrutiny. “I think it’s very conceivable that we could start seeing challenges under many BITs as Canada embarks on a path of introducing protectionist measures under the Liberal administration,” Swick says.

It’s not that Canadian legislators are blind to cultural protectionism. Various exemptions for these industries are expressly provided for in Canada’s BITS and NAFTA. They cover not only print publications but their distribution; the production, distribution, sale or exhibition of film or audio, video and audio music reporting; radio communications intended for reception by the public; all radio, television or cable broadcasting undertakings; and all satellite programming and broadcast network services.

The exemptions cut a wide swath. United Parcel Service of America (UPS) discovered just how wide when the company filed a US$160-million NAFTA claim in 2000. UPS alleged that Canada had provided improper subsidies to Canadian publications that gave Canada Post an advantage over private courier services. Seven years later, the tribunal ruled against the UPS, holding that the cultural industries exemption, which it called “admittedly broad” and “expansive,” applied.

The difficulty with the exemptions is that they differ, and to varying degrees. NAFTA, for example, allows the United States to retaliate if Canada invokes the exemptions. Many BITs, like the one with Egypt that governs the GTH dispute, were negotiated in a world that perceived money moving just one way: from developed to developing countries. The upshot is that many were not drafted with protections for the developed country in mind.

That, obviously, has changed. “In the past, Canada may not have thought about cross-investment when it was negotiating trade treaties, but global money has no need for a home anymore,” says Barry Appleton of Appleton & Associates in Toronto. Unlike some European countries, Canada has not taken any step to update its BITs.

Going forward, both CETA and the TPPA maintain the cultural exemption for Canada. “These new agreements are not aspirational but recognize what’s actually going on in the world by allowing more protectionism for everyone,” Appleton says. “In doing so, they give government more latitude to discriminate against foreigners in their public policy.”

The lawyer, however, also maintains that both CETA and the TPPA were conceived and drafted too hastily, without sufficient consultation. “The treaties have lots of holes and problems generally, and eventually these errors will manifest themselves into disputes.”

WHAT WILL CHANGE DRAMATICALLY, at least under CETA, is the way in which disputes will be resolved — and the issue could not be more controversial.

When the European Commission invited comment on investor-state arbitration in 2014, the 145,000 responses crashed its computers. The respondents were overwhelmingly against the current system, essentially a private one, where arbitrators appointed and paid for by the parties are the adjudicators. But it’s not just Europe. Many countries, including Canada and the US, are seeing a backlash against investor-state arbitration in its current form, where the mechanism is often viewed as an infringement on sovereignty. Other criticisms of the current system are the lack of judicial independence and the lack of standing for third parties who may have an interest in the proceedings.

The upshot is that the final text of the Comprehensive and Economic Trade Agreement, signed in February 2016, does away with arbitrators appointed by the parties and replaces them with a permanent tribunal roster established by governments with no input from investors. The 15-person roster will be composed of five Canadian members, five from the EU and five from other countries. Arbitrators will be selected randomly from that group. “The roster will enable Canada and the EU to control which experts sit on arbitrations to ensure that they are sensitive to government perspectives,” writes Greg Tereposky in a Borden Ladner Gervais LLP bulletin.

CETA also establishes an appellate tribunal to review awards. Its jurisdiction will be limited to errors of law and manifest errors in fact. “This will without doubt improve the consistency and predictability of the interpretation and application of investment protection provisions,” Tereposky states.

Cicchetti, for her part, is skeptical that a permanent court is the right way to go. “The parties won’t have an opportunity to choose the decision-maker, and who knows just how these people will be chosen?”

But professor Gus Van Harten of Osgoode Hall Law School at York University says that the CETA arrangement is a definite improvement and augurs well for Canada. “Canada has been gung-ho on accepting the old system even when it’s the country in the more vulnerable position, as it did when it signed on to NAFTA. Since then, we have led the pack among Western nations in ceding sovereignty.”

Cases like GTH, Van Harten adds, are now exposing risks that Canada did not expect when it signed the BIT with Egypt. “Even if the risk of losing is small, there’s a potential for a $1-billion award for lost profits,” he says. “Surely that’s enough to impact decision-making in this country.”

WHAT, THEN, LIES AHEAD for investor-state arbitration? Is Canada going to see a decided uptick or not?

Generally speaking, as BITs have proliferated globally — there are now just under 3,000 in force — so have the number of investor-state disputes. ICSID, which hears an estimated two-thirds of BIT disputes, administered 38 in 2011. That number, itself a record, gave way to a new high of 52 cases in 2015. Growth has been particularly noticeable during this century: just 69 cases were registered between 1972 and 1999, while some 500 were registered between 2000 and 2015.

Sheer numbers suggest that CETA could in itself contribute to an upsurge in arbitrations involving Canada. When and if the treaty is ratified by all parties, Canada will effectively have a BIT with every one of the EU nations, including the original EU members, with whom it currently has no investment-protection treaties.

The reforms envisaged by CETA to the arbitration system could contribute as well. “I think if the reforms that are proposed are actually put into place, they could have a significant impact on arbitration claims,” Van Harten says.

Bartuciski also believes that the trend will continue, but that CETA and TPP will in themselves not be significantly influential in increasing the number of disputes. “The changes that these treaties make to the investor-protection regime are quite modest, and what we’re basically looking at is a NAFTA-type regime with the wrinkle of a permanent court.”

Gibson’s view is that a huge wave of investor-state claims is not in the offing. “They’re expensive, they bring a lot of publicity, and investors know that states win most of the claims, so there are only a certain number of claimants who will resort to arbitration.”

But there may be a wild card in the mix: third-party litigation funding has made its way to investor-state disputes. Companies like the $300-million Burford Group, the world’s largest private litigation funder, and Calunius Capital, both based in the United Kingdom, are now providing financing. “Investor-state disputes are attractive to third-party funders because they always involve big dollars,” says Robert Wisner of McMillan LLP in Toronto, who represents a number of junior mining companies who have obtained such funding for ICSID cases.

Third-party funders don’t care much whether the complainant is based in developing country or a developed one: all they really care about is whether the case has merit and whether they can recover any award. Indeed, financing a claimant from a developing country may be more attractive to third-party funders because the prospects of actual recovery from developed countries is a much safer bet than trying to collect from poor countries. The upshot is that third-party funding could be a game-changer in the investor-state dispute arena.

So what’s next? If it works for Egypt, why wouldn’t it work for Burundi?

Julius Melnitzer is a freelance legal-affairs writer in Toronto.