On November 30, 2023, Bill C-59 (the “Bill”) received first reading in the House of Commons. The purpose of the Bill is to enact certain tax proposals from the recent fall economic statement, the 2023 federal budget and other previously announced measures. Included in Bill C-59 is a further-updated version of the proposed 2% equity buyback tax (“Buyback Tax”). Although not strictly speaking an income tax, the Buyback Tax will be included in the Income Tax Act (Canada) (“Tax Act”) as the new Part II.2. The Buyback Tax will apply to relevant transactions that occur on or after January 1, 2024, and does not include a safe harbour for equity issued prior to that date. Given its inclusion in Bill C-59, it is highly unlikely that the Buyback Tax will undergo any further changes prior to its enactment.

The draft legislation implementing the Buyback Tax was previously released by the Department of Finance on August 4, 2023 (“August Legislation”) which was, itself, a revised version of the initial rules introduced as part of the 2023 federal budget. The current version of the Buyback Tax rules is largely the same as the August Legislation but there are some useful refinements, the most significant of which are noted below. Despite these changes, the scope of the Buyback Tax remains broad and it will likely apply to a variety of ordinary course capital market transactions including, in particular, normal course issuer bids and substantial issuer bids. Capital markets participants will therefore need to carefully consider the Buyback Tax when evaluating transactions that involve the redemption, repurchase or cancellation of publicly traded equity.

Who does the Buyback Tax apply to?

The Buyback Tax will apply to a corporation, trust or partnership that is a “covered entity,” a term which has been defined to include publicly listed Canadian resident corporations, real estate investment trusts, specified investment flow-through (“SIFT”) trusts, and SIFT partnerships. For these purposes, “equity” is defined to mean a share of a corporation, an income or capital interests in a trust or an interest as a member of a partnership.

How is the Buyback Tax calculated?

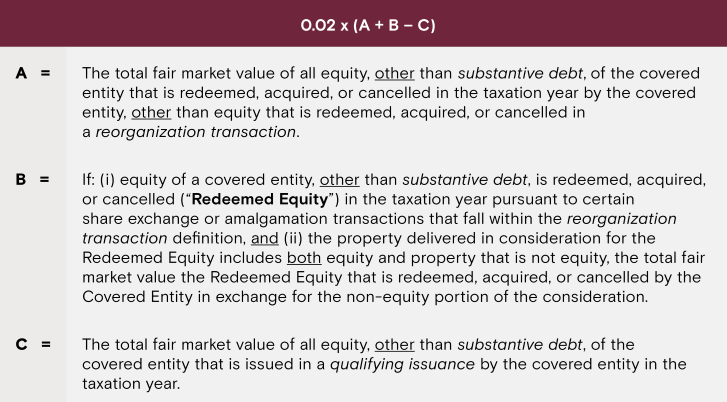

In general terms, the amount of the Buyback Tax is equal to 2% of a covered entity’s net equity repurchases in the taxation year. More specifically, the Buyback Tax is computed by reference to a formula, a somewhat simplified version of which is set out below:

Note, a “qualifying issuance” is defined for the purposes of variable C of the above formula to include the portion of a particular issuance of equity by a covered entity that is made: (i) in exchange for cash and/or a convertible note, bond or debenture issued by the covered entity, or (ii) to an arm’s length third party in exchange for property that is used in the covered entity’s active business.

The Buyback Tax rules contain a de minimis rule such that a covered entity will not be subject to the tax in any taxation year in which the total of the amounts determined for it under variables A and B is less than C$1,000,000.

Exceptions to the Buyback Tax

There are two conceptual exceptions, which, if applicable, will result in equity of a covered entity being excluded from the Buyback Tax formula. These two exceptions are summarized below.

- Substantive Debt – While this term is comprehensively defined in the Buyback Tax legislation, it is intended to capture equity that possesses debt-like characteristics (namely, limited voting, non-convertible, non-exchangeable, fixed value preferred shares).

- Reorganization Transactions – Conceptually, this exception applies to certain transactions that technically include a redemption, acquisition, or cancellation of the covered entity’s equity but that do not from a policy perspective warrant being included in variables A or B of the Buyback Tax formula. In most cases, the exception is triggered when the investor does not decrease his/her financial investment in the covered entity (or one or more successor entities). The term “reorganization transaction” is defined in detail in the Buyback Tax legislation but generally includes equity that is repurchased, redeemed, or cancelled in the course of a wind-up, an amalgamation or equity exchange whereby a holder receives consideration that includes equity, as well as so-called “butterfly transactions” covered by subsection 55(3) of the Tax Act.

Anti-Avoidance Rules

The Buyback Tax provisions contain specific anti-avoidance rules which, in general terms, prevent the following transactions from reducing the amount of tax payable by a particular covered entity under the rules:

- Equity issuances or repurchases by a covered entity that are part of a transaction or series of transactions the primary purpose of which is to manipulate the Buyback Tax formula.

- Repurchases of equity issued by a covered entity by an affiliated corporation, trust, or partnership where the covered entity controls the affiliate or (ii) owns, directly or indirectly, more than 50% of the equity of the affiliate.

Changes Relative to August Legislation

As noted above, while the current version of the Buyback Tax is largely unchanged from the August Legislation, the Department of Finance has fine-tuned certain aspects of the rules. The most notable changes are:

- The current version of the Buyback Tax rules deals more effectively with share exchange and amalgamation transactions in which equity holders receive both equity and non-equity consideration. This has been achieved by: (i) expanding the scope of the “reorganization transaction” definition so that it does not automatically exclude mixed consideration transactions, and (ii) adding new variable B to the Buyback Tax formula which, in general terms, only subjects to tax that portion of the equity that was redeemed, acquired or cancelled by the covered entity in exchange for non-equity consideration. In contrast, under the previous version of the Buyback Tax rules, the reorganization exception generally applied to share exchange and amalgamation transactions under which equity was the only consideration received by equity holders on the exchange.

- Similarly, the latest version of the Buyback Tax rules deals more fairly with equity issuance transactions in which the property received by the covered entity includes a non-cash component. In general terms, under the revised rules, the fair market value of any portion of an equity issuance (other than one involving substantive debt) for which the covered entity receives cash consideration will reduce the base on which the Buyback Tax is imposed. In contrast, under the August Legislation, a covered entity generally received relief under the Buyback Tax formula only when it issued equity exclusively for cash consideration.

- The definition of “covered entity” has been revised to exclude exchange traded funds whose investments would otherwise bring them within the confines of the definition.

- The redemption by an open-ended unit trust of its equity pursuant to its terms will generally be excluded from the scope of the Buyback Tax (as a result of including such a transaction in the reorganization transaction definition) provided that the redemption occurs at the demand of a holder and the redemption proceeds do not exceed their fair market value at the time of redemption.

- The definition of “substantive debt” has been broadened to include equity with: (i) voting rights, provided that such rights do not apply to the election of the board of directors, the trustees, or the general partner (as applicable) of the covered entity, except in the event of a failure or default under the terms or conditions of the equity, and (ii) fixed dividend or distribution entitlements.

- The redemption of equity by a covered entity pursuant to the exercise by the equity holder of a statutory right of dissent (again, as a result of including such a transaction in the definition of a reorganization transaction).

Observations

The Buyback Tax was likely inspired by a similar 1% tax that was implemented in the United States at the beginning of 2023, but the underlying policy rationale for the tax is less clear. According to the Department of Finance, the purpose of the Buyback Tax is “to make sure that large corporations pay their fair share [of tax], and to encourage them to reinvest their profits in workers and in Canada.” While reasonable people can differ as to whether public corporations pay enough tax, it is troubling that the federal government seems to think it is better positioned than a business to determine how its surplus capital ought to be allocated. This mindset also seems to presuppose that the funds received by investors on an equity repurchase transaction will not be reinvested in a productive manner. Perhaps the Department of Finance simply wanted to add to its assortment of revenue tools in order combat the deficit – it has been estimated that the Buyback Tax will raise on average C$500-600 million per year in revenue over its first five years of existence. While this is not an immaterial amount of money, when viewed in the context of the federal government’s total annual revenues of approximately C$457 billion (for its 2023-2024 fiscal year) it is not a significant amount either. Finally, the federal government may be of the view that equity repurchase transactions provide inappropriate tax advantages to shareholders relative to the payment of dividends. Again, what is and is not appropriate from a tax policy perspective is a subjective assessment, but it should be noted that, at least in the case of a substantial issuer bid, a significant portion of the purchase price is often characterized as a dividend for Canadian income tax purposes.

Careful consideration

Capital markets participants will therefore need to carefully consider the Buyback Tax when evaluating transactions that involve the redemption, repurchase or cancellation of equity by publicly traded entities.

Read more on tax law and legislative updates on the Stikeman Elliott website here.

***

Jonathan Willson is a partner in the Tax Group. His practice focuses on all areas of Canadian income tax law, including domestic, cross-border and international mergers and acquisitions, corporate reorganizations and restructurings, corporate finance, and investment fund structuring.

Jonathan’s clients include publicly listed and private Canadian, U.S. and global entities across various industries, including financial services, real estate, mining, technology, and healthcare.

He has been recognized as a leading lawyer in the areas of tax, corporate tax and derivative instruments by the legal industry’s most notable directories, including The Canadian Legal Lexpert Directory and The Best Lawyers in Canada.